Work from Home

David Leblanc is feeling fitter, happier, more productive.

I spent most of grad school writing a 50,000 word thesis on games about work, and the very messy entanglements between work and play they entail, from the position that the two constructs are separate parts of life. So I was a bit shocked—or at least mildly bothered—when I stumbled upon a quote from psychologist Brian Sutton-Smith that has widely circulated among game scholars and self-help bloggers: “The opposite of play isn’t work. It’s depression.” At first, I was reluctant to accept an alternative version of the formula I had used before. But in truth, it’s precisely by taking work and play not as isolated constructs, but as opposing vectors that intersect in key places, that we can actually understand the games that endeavour to combine the two in creative ways. It’s this stance that affords us the possibility to question, as Ian Williams puts it, why we play at hard work. What makes the topic of games about work so irresistible is precisely the tension between the oppositional qualities of work and play, and the curious fact that, at the same time, they share so much.

The work games I’ve been interested in are predominantly invested in forms of management. These games approach work from a bit of a distance—the cold, and perhaps familiar, eye of the planner. You could call these simulators, in the SimCity sense, which is a fair assessment. But not all work games necessarily appeal to sim enthusiasts. In fact, what makes them unique(and, I keep telling myself, worth studying) is the fact that they often eschew realism in order to reproduce the structures, systems, and managerial logic of work into a form of play. In doing so, such games throw the seemingly opposite regimes of work and play into sharp relief.

Over the years, I’ve maintained a few vices in this area, chief among them Stardew Valley and Factorio. These games, invariably, put you to work. They’re particularly interesting cases because they allow players to exercise total managerial control over the perennially privileged sites of production: the farm and the factory. Take away the social hub element and Stardew is a fairly straightforward farming game. In my experience, it was one in which I researched the highest-yield crops and labored to create the optimal arrangements of seasonal crops around sets of automated sprinklers—a must-have for the optimal farming process. Ultimately, the process had the zest of a spreadsheet more so than a garden. Factorio shares this element of pure rationalization, or optimization, that made Stardew click for me. In this factory-building game, I would harvest the natural resources of an alien planet in order to build increasingly intricate clockwork systems of automated production lines, with the goal of launching a spaceship off the rock. But really, it’s a taxing grind of continually improving upon the vast network of factories, of thinking and planning ahead, of finding creative ways to make things work better, and faster. Of being more productive.

Every element of the factory can be improved upon to make it more efficient and better integrated with other systems: a savvy factory planner can maximize their throughput by strategically connecting different resources to the same conveyor belt, or implement a smelting farm in just the right configuration such that the path from raw mining to material processing is the shortest. If ambitious, they can add railway systems to connect long distance resource operations. You’re always striving towards that perfect ensemble of machines—a totally optimized engine of production. In each game, optimization and moreover, productivity is the center of attention.

So, to return to the question asked earlier, why do we play them? For one, I’d resist claiming that we play farm or factory games because these industries have undergone fundamental transformations in the last century, and have essentially progressed to a point where they operate without people. That’s both too easy of a claim to make, and too difficult of an argument to defend. There’s another way of approaching the question that speaks directly to the games themselves and the way we relate to them instead of making overly-literal connections to the industries they simulate.

The reason we play hard work is because the games allow us to enter into a state of continuous productivity. They’re games about production—making things—but even more importantly, they’re games about productivity—finding the optimal way of making things. And doing so, importantly, by giving players end-to-end control of the process. Between the growing casualization of formerly stable jobs and the multitude of ways workers are subject to the inefficient systems they deal with daily, there’s an urgent need for people to feel productive on their own terms. Stardew Valley, Factorio, and the many games like them may put us in control of industries in a way that now only exists in our imagination. But as games deeply rooted in the present moment, they capture the concerns and anxieties dredged up by work as we know it today. Ultimately, as various forms of labor become routinized, more precarious, or just plain bullshit—and as workers around the world stage important interventions to that effect— it’s no wonder that work games would enjoy success in allowing people to enjoy the pleasure of being productive, and of actually taking ownership over the time and products of that labor.

Time and time again, players have described Factorio as addicting. From facetious confessions (“I used to have a family, now I have a factory”) to words of caution (“be warned: it is very possible you will become hooked on this game”), user reviews are loaded with mentions of obsession and addiction. The way I see the relationship between the games and the obsession its players nurture is precisely indebted to that paradigm of productivity which many either lack in their everyday life, or require in excess. As someone who thrives off that feeling of productivity, a game like Factorio may very well be pure cocaine.

Work games, by virtue of replicating the forms, systems, mechanics, and often feelings of work that is necessarily fulfilling, put the relationship between work and play into question. Moreover, they problematize a foundational definition of games—that is, that they are unproductive. In Man, Play, and Games, what is considered by some to be the first entry in the field of games studies, Roger Caillois defines games as “Unproductive: creating neither goods, nor wealth, nor new elements of any kind.” The professionalization of e-sport players, gray markets of virtual economies, the emerging careerism of live streaming games—these are but a few examples of the way in which games and the cultures surrounding them have turned productive. Yet games like Factorio, Stardew Valley, and the myriad others like them, trouble that categorization even further: they’re made for us to feel productive.

In truth, that desire to feel productive has a word. For a long time, thinkers of the Marxist persuasion—and of Italian autonomism, specifically—have termed it the social factory, or the social reproduction of capitalism, wherein our lives are in continuous integration with the reproduction of capitalism. In effect, it’s the games that put us to work that give us much-needed perspective on our toxic desire for continuous productivity.

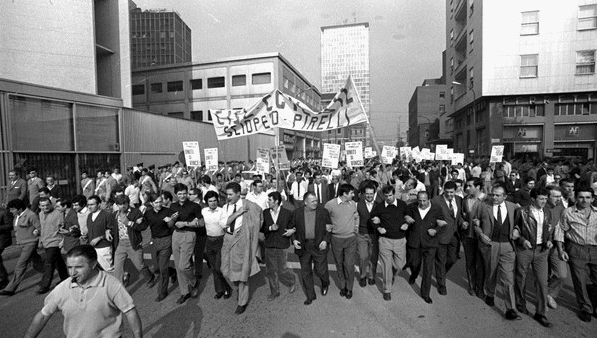

Source: https://libcom.org/library/our-operaismo-mario-tronti

Incidentally, I’ve come to recognize the weeks I spend more time and energy on bettering my virtual farm or factory than on bettering myself as periods of depression. When getting anything done becomes a challenge, there’s always a conveyor belt to upgrade, or better crop arrangements to test out—anything to at least give the semblance of being functional, productive. Although the opposite of play may be depression and not work, oddly the combination of work and play lends itself curiously well to the depressed.

We play hard work not only because it is designed to be fun, engaging, and rewarding, but because the cultures and regimes of labor are so deeply familiar, reassuring, and embedded in the fabric of everyday life. Despite our better judgement and will to devote at least some of our time to being unproductive, we play hard work not only because we like to play, but also because we like to work.

David Leblanc is an editor here at Haywire. He lives in Montreal, where he works in communications and still plays Factorio, curiously, to unwind. For more on work games, you can read his Master’s thesis, or the many other takes on the topic. Sometimes he tweets.