Summer, Fall, Winter, Spring

Joel and Ellie’s year of survival and brutality made one of the most profound statements on violence in games. By Andrew Huntly.

Nathan Drake has killed a lot of people.

In any other medium, Drake would be considered a sociopath at best and a war criminal at worst. His nearest contemporary, film’s Indiana Jones, also has a hefty bodycount, but it doesn’t even come close to the pile of corpses Nathan Drake has accumulated over the course of five Uncharted games. If ever there was a posterchild for the term ‘ludonarrative dissonance’, it would be Mr. Drake. It’s a testament to Naughty Dog’s writing chops that our impression of him is that of a witty, energized adventurer rather than a mad, self-centered killer.

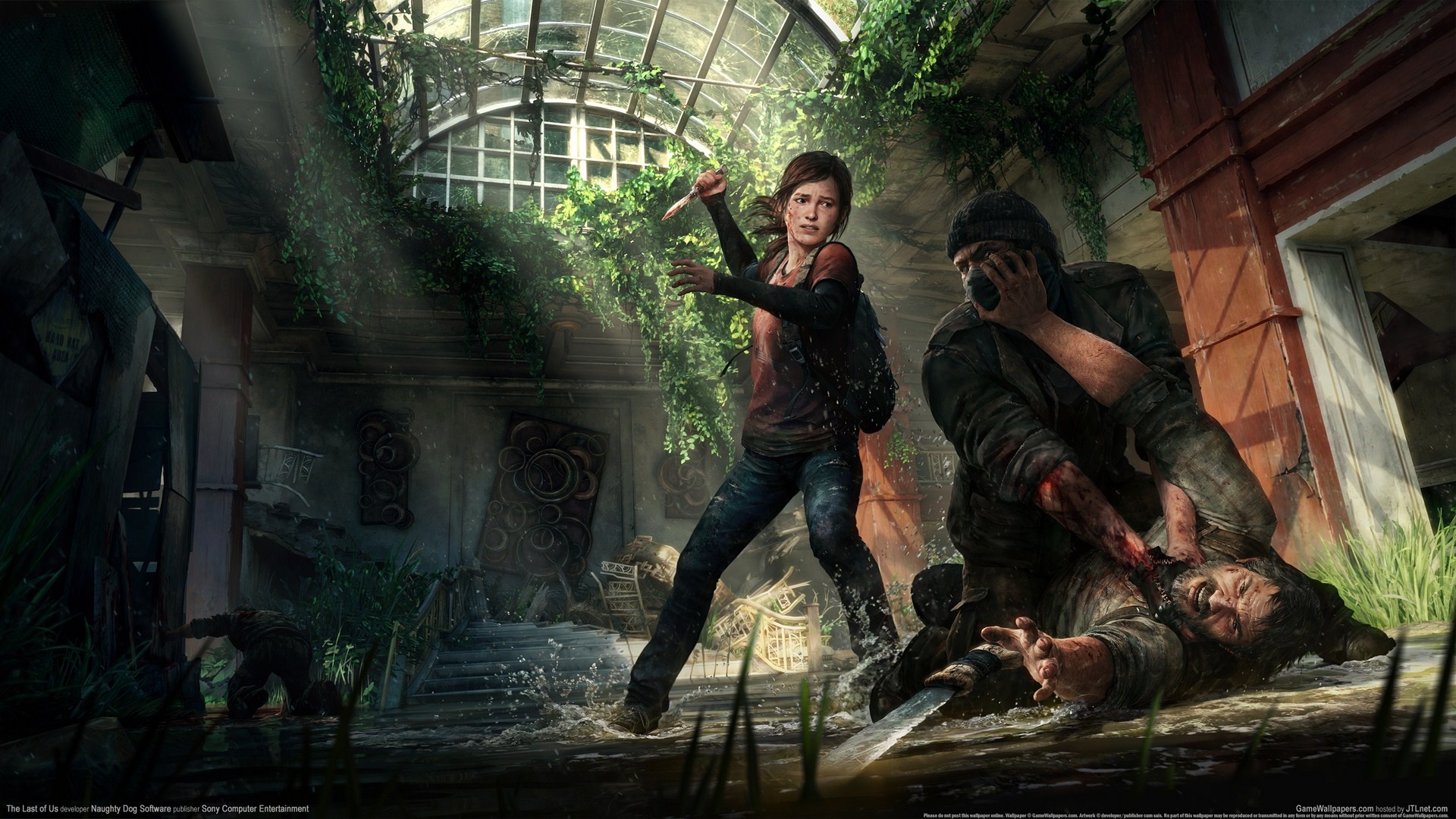

And it speaks even more to the writing of Naughty Dog that The Last of Us completely overcomes what Uncharted never did. Its lead protagonists Joel and Ellie also kill, and in far more violent fashions than anything Nathan Drake could ever conjure up. Throughout their adventure, they shoot people, they stab people (repeatedly), they beat people with both blunt instruments and their hands, they set people on fire, they strangle people and they straight up execute people. And yet, the level of violence adds to the story and characters in ways that few games even dare try to execute.

Set 20 years in the future, The Last of Us shows humanity in ruins after the outbreak of a deadly fungal infection. The surviving populace lives in militarized quarantine zones, unaffected areas of major American cities. While the infection is kept at bay, the inhabitants are their own worst enemy, forming loose gangs centered around a currency of ration cards and munitions. When something goes wrong, things quickly descend to violence. The beginning of the game tasks Joel with hunting down the man who stole a gun shipment from him, brutalizing his way through to gather further tools of violence.

This is the game at its least justifiable in regards to force. It breaks down the acts of gunplay and stealth kills into tutorials, marring immersion with button prompts splashed on the screen. It doesn’t take long before these more overtly game-like elements are dropped. Removed from this instructional phase, violence in The Last of Us is unflinching, graphic and brutal. The small taps on the controller produce moments of unparalleled viciousness. Never has a melee system felt so crunchy and satisfying, whilst also being so repulsive and gruelling.

This is the game at its least justifiable in regards to force. It breaks down the acts of gunplay and stealth kills into tutorials, marring immersion with button prompts splashed on the screen. It doesn’t take long before these more overtly game-like elements are dropped. Removed from this instructional phase, violence in The Last of Us is unflinching, graphic and brutal. The small taps on the controller produce moments of unparalleled viciousness. Never has a melee system felt so crunchy and satisfying, whilst also being so repulsive and gruelling.

Unlike last year’s Spec Ops: The Line however, The Last of Us does not aim to shame or criticize what it portrays, and instead uses violence as an honest tool to flesh out its world and characters. Joel is not your traditional idea of a good person, even the word ‘antihero’ is something of a stretch. But he is a believable, well realized character and the violence he performs on other people is a natural part of the world as he and Ellie know it. Killing is neither a pleasurable nor a cathartic experience, but it feels necessary. It doesn’t feel good, and at times feels genuinely unpleasant, but the story and context ground it so heavily that there is meaning and weight in every little act of bloodshed. The fact that it’s so natural to Joel never feels like the realization of a power fantasy, but rather enhances the frightening reality of this world and how it’s shaped his character. When choking an enemy to death, he slaps Joels arms with deadening hands, his eyes bulging wide and a croaking gasp breaking from his lips. All you wish is for it to be over.

What’s truly interesting is how this level of violence purposefully clashes with the landscape of The Last of Us. Most post-apocalyptic visions concern themselves with dry, barren wasteland. The world of McCarthy’s The Road has no vegetation. The Fallout games are similarly sparse, even their water being undrinkable. Meanwhile, the America presented in The Last of Us simply doesn’t care that humanity is dying and carries on, business as usual. Vegetation is lush, crawling up buildings and scattering the streets. Marshes have formed where roads once were. Forests are teaming and bursting with life. Animals of all shapes and all sizes are thriving, roaming in herds across this beautiful world, in which humans are slaughtering and eating one another, just for another few days of life. It’s an animalistic portrayal of the remnants of society, and this further enforces the graphic violence. The belief that we’re above all other creatures comes toppling down when food and shelter begin to run low.

We frequently see complaints, from inside the industry as much as out, that games are far too violent. That the focus is always on violence, the gameplay objectives always revolving around the act of killing. But The Last of Us brings up an interesting point – perhaps the issue of violence in games isn’t its quantity, but its honesty. The Last of Us is an extraordinarily violent game, its depiction of death unflinching. But it’s always grounded, always mired in its troubling and dark story. There is no sense of relief to killing, nor any sense of condemnation. The violence is true to the characters and true to the themes of the game. This is not about catharthis, it’s about using a familiar tool to tell an unfamiliar story.

We frequently see complaints, from inside the industry as much as out, that games are far too violent. That the focus is always on violence, the gameplay objectives always revolving around the act of killing. But The Last of Us brings up an interesting point – perhaps the issue of violence in games isn’t its quantity, but its honesty. The Last of Us is an extraordinarily violent game, its depiction of death unflinching. But it’s always grounded, always mired in its troubling and dark story. There is no sense of relief to killing, nor any sense of condemnation. The violence is true to the characters and true to the themes of the game. This is not about catharthis, it’s about using a familiar tool to tell an unfamiliar story.

It’s a bold move from Naughty Dog. The overall excellence of the Uncharted games overcame their disconnect between the witty hero and the cold murderer, but The Last of Us brought the characters and the violence together. Joel and Ellie are both thoroughly likable, but both are flawed, sculpted by a messy world that forces people into acts that are as despicable as they are frighteningly necessary. They, like Nathan Drake, have killed a lot of people. But it all meant something.

Andrew Huntly’s cinematic rants have been complimented on British radio shows and their associated podcasts.