Rain World and Indiepocalypse

Ron So on hostile ecosystems.

How do you survive in the post-apocalypse? As far as games go, it’s base-building, exploration, crafting. You find, you scavenge. Zombies, wildlife? Fend ‘em off. Then there’s the human element: who’s friend, and who’s foe? You need to figure it out quick.

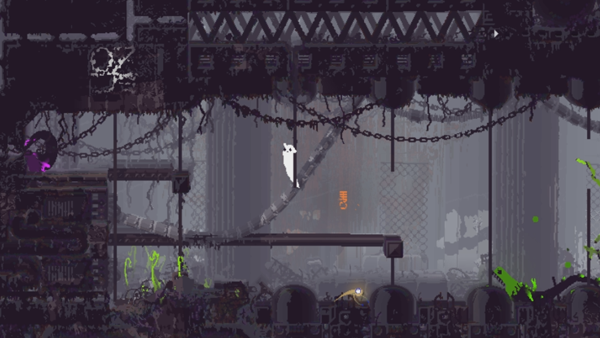

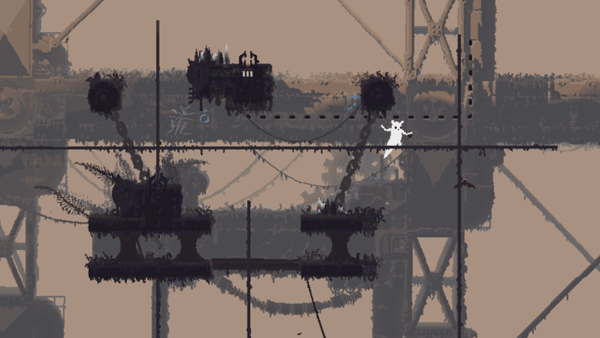

What if there aren’t humans anymore though? In Rain World, you’re a slugcat, a small nimble creature in a wasteland of industrial ruin that’s been reclaimed by wildlife. You don’t stick around long enough to craft. There are tunnels and shelters, prebuilt, and also broken bridges and rusted pipes and corroding statues; you see all this in your journeys, and you don’t wonder why they’re there. You have other concerns. You wake up, look for food, avoid being eaten, and find a place to sleep, all before the Rain comes. It’s not easy. There’s a vast, unyielding ecosystem out there, and it’s up to you to figure out how to navigate it. It doesn’t care for you, and you will not conquer it. You need to learn, need to adapt. You have to, to keep going.

Okay. Back to human. What if instead, you’re trying to survive in the post-Indiepocalypse?

That’s the world Rain World developer Videocult finds itself in. They had a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2014, raising USD $63,255. Their game was launched three years later on Playstation 4 and Windows. The ‘Indiepocalypse’—or at least concerns over it—really reached a fever pitch during that time, and have hardly subsided since. The term refers to the fact that more and more games are hitting platforms; smaller devs worry that their releases won’t be able to draw enough notice. Steven Wright wrote about it last year for Polygon, and interviewed several devs about how to best survive in a flooded indie market in flux. Liz Ryerson argued in a response article for Deorbital that this explosion of games wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. There had been too much focus on sustainable business ideals before, she wrote, and not enough on actually producing art. Rain World was an example amongst many she cited that showed you could release a game with a unique, creative vision, not just in spite of this shifting post-Indiepocalyptic landscape, but maybe even stronger for it; without the siren songs of indie stardom or replicable market solutions, perhaps the industry would be able to find a better path forward, to embrace new voices and ideas. But that’s an end goal, not a road map, and in the meantime Videocult, not unlike the slugcat they created, still have to navigate the unforgiving, uncertain territory in front of them.

Players don’t generally get a sense of the journey a game goes through during development. We only see what’s in the end product. When I first started a new game in Rain World last year, the first thing I saw was a slugcat selection screen. The default choice was the yellow Monk, which was described as a more peaceful experience. Pressing right, there were two more options, but I went with Monk without much thought. The easy mode equivalent seemed like what I’d want, based off of what I’d known then about the game.

I’d seen some eye-catching gifs from its Kickstarter campaign, but most of what I knew of Rain World were fuzzy recollections of a Quick Look video on it from Giant Bomb. Brad Shoemaker’s commentated playthrough made it seem incomprehensible: the world teemed with predators, it was easy to get cornered, guidance consisted of indecipherable symbols, and the controls seemed imprecise at pivotal moments. His slugcat died constantly and got nowhere. Brad was frustrated, and also a bit intrigued and unsure about it all, but my takeaway was that this might not be a Game For Me. Even with that, though, it looked unique, with a great atmosphere and an apparent commitment to a vision, and I did finally decide to try it out. It was in a Humble Dystopian bundle, $5 for it and six other games, so hey, why not? But I didn’t expect to get far.

Rain World quickly hooked me though, and refused to let go. Its world was mysterious, surprising and alive, and I died a lot but kept going. I grew attached to my lil’ yellow slugcat, and then I started thinking back to all the prior footage I’d seen. Hadn’t those all featured a white one? Where did my yellow slugcat come from? I checked, and sure enough, Giant Bomb’s video had a white slugcat, but no mention of any difficulty choice. That, apparently, had been patched in December 2017, v1.5, about nine months after the Giant Bomb video and 11 months before I played it. There was a red new game+ Hunter added with the yellow Monk, and the original white slugcat was recast as the Survivor and placed in the middle. As I continued playing, I started to wonder how different this Monk was. What had other people’s experiences been? I began looking at reviews and patch notes to try to figure out where the changes had come from.

Most games media coverage on Rain World came out around its March 2017 release, I found, including Giant Bomb’s video. Mixed reviews generally agreed: novel ideas, world, creatures, but finicky controls, overly punishing. Obtuse. Niche. There was little press after that. Only one in-depth article I found even mentions the Monk: in that piece for Unwinnable, Levi Rubeck, like many of those reviewers, found the game frustrating and arbitrarily punishing, playing on Survivor. He ultimately gave up. If he ever went back, he wrote, maybe he’d restart on Monk instead.

That arbitrary, punishing uncertainty is what separates Rain World, and seemed to put people off. All of Rain World’s creatures have their own survival needs, and accordingly don’t stay in place. The world keeps shifting, even as you die, and the path you scouted before will suddenly be blocked by a ravenous lizard, or the spear won’t be there, or the Rain comes earlier than you expect. We’ve seen discussions before about whether making difficult games easier might expand audiences or dilute core visions, with Dark Souls and Hyper Light Drifter. Those games have easily-understood difficulty though, at least on the ground: you understand what killed you, and you can learn and adapt to hand-placed enemies and repeated attack patterns. In Rain World, your squishy slugcat will die suddenly, and often. And sometimes, you don’t learn, you just die—unfairly, cruelly, repeatedly. You can’t rely on your experience of how the world was before; you have to adapt to what’s in front of you.

Videocult put out patch v1.01 less than two weeks after release, in response to the early feedback. Some of the changes addressed specific frustration points that players and reviewers had brought up. Deaths would be slightly less punishing now: map progress is no longer reset by death, and exhausted food sources would slowly regenerate through deaths so players wouldn’t get stuck and starving in a food-scarce area. Videocult emphasized in the update that they wanted to take care of “low hanging fruit” and see the player response first, because they didn’t want to overcorrect and take away from the concept of the game. The game should be existential, unfair at times even, and that was the point. But that point still had to reach players, and how many chances now does a small game have to make its mark? There’s always another game on the horizon.

The thing is, I think most of those reviewers “got” what Videocult had been going for. They just weren’t willing to see it through. Rain World early on establishes its cycles of death and despair, takes its toll and keeps on taking. The game was unique, but along review paradigms, it was hard to recommend overall, because many players maybe wouldn’t enjoy the endeavor. Can a game be artistically successful if it communicates its themes, but most people don’t think it’s worthwhile to see it through? What’s the acceptable threshold for player drop-off, in a game that feels so set on thinning the herd? These are questions without set answers; you just have to make a decision and go. I think that’s maybe what’s so scary for developers: the uncertainty that extends in all directions. You can’t rely on anyone’s experience of how the world was before, and it can feel like all that pulled you through was persistence and luck. Even if you do find a successful path, you couldn’t retrace those steps if you tried. The world keeps shifting too much.

On their Kickstarter page, Videocult links to the TigSource devblog which they posted to all throughout Rain World’s development, and you can see all the changes it’s gone through, even pre-Kickstarter. There’s some fascinating stuff posted there as the concept takes shape: some of the commenter arguments mirror the ones reviewers would later grapple with, about the lines between challenge, frustration, fun, and forgiveness, about whether mechanics like the rain timer or area gating were vital to what it was. All the way back in 2012, they first posted about a prototype for Rain World, consisting of one room with bats to chase and lizard to be chased by. The slugcat was there, fluid movement and all, a constant throughout development even as the world around it grew more complicated.

Studios can—maybe even have to—rapidly adapt now, to the market and to feedback, with patches, and as-services. Maybe the best summation of the intent behind these update cycles comes in this dev post by one-half-of-Videocult James Primate (the other being Joar Jakobsson) on July 8th, 2016, a year before Rain World’s release:

“One thing that we’ve sort of been aware of for a while but now is very clear: we basically made the game that we wanted to make, but now have to make several other easier to understand games within that game, because our version of the game is too loose and indecipherable. This isn’t a bad thing at all really, as it means that the finished version is going to be much closer to *actually playable* and so vastly more people will be able to have fun. And none of that takes away from “our game”, which is still 100% there and will exist for high skill players to discover.”

What all developers are trying to do is find a path between the game they envision, and the ones the players see. Videocult eventually decided the best way to keep their version and their vision of Rain World intact was to encase it in the white Survivor slugcat and to add the yellow Monk as one that more people could see through. Games aren’t immutable experiences anymore, and the one those reviewers documented isn’t the one I got. You can look at what was there before, but you can’t rely on it.

All those versions of Rain World might differ, but the basic idea of its unrelenting world remains. Say there’s a lizard in your way, blocking the path forward. You die to it, repeatedly. You can blame the lizard, or the dev who put it there. But in Rain World, you cannot dwell. You have to keep moving, before the Rain comes. There are things which you can’t affect, things that can’t be overcome, and others which you can’t understand. Will you keep going, to push past? Can you let go of notions of balance or a natural progression to things?

Rain World never felt like it was interested in following standardized paths to success. And there’s no set path—or end—to art either. The Indiepocalypse might be making the former harder to see, and perhaps that does clear the way for bold new visions. Or maybe we’re headed for collapse, because even as the smaller studios scrap to subsist, the system as a whole is incomprehensible, unfair, unsustainable. Some slugcats might endure, but whoever built the infrastructure and brought it down will leave only echoes.

Videocult seems to want to keep adapting their game for players, even as the platforms shift around them. Kickstarter is a questionably viable avenue now for indies trying to follow their path, but if the timeline was pushed forward, maybe Rain World would’ve been Early Access instead. There’s Epic, challenging Steam’s dominance with exclusivity deals and more equitable revenue splitting for developers; they announced their new Game Store as a “worldwide digital commerce ecosystem,” but pull back and it’s also fighting tooth and claw for its own place in the greater games ecosystem. Subscription services are slowly taking hold, and there are external factors like an economic crash or anti-net neutrality that could wipe out large swaths. The Playstation Vita died, and seems to have taken a previously announced port of Rain World with it, but the Nintendo Switch seems like the hot new indie game platform developers are pinning their hopes on now. Videocult released a port for it late last year, setting off another wave of reviews, and when those Switch players start a new game, they’re going to be presented with the Monk option first, just like I was. Meanwhile, some Kickstarter backers are still clamoring for previously promised Mac and Linux versions, and feeling left behind. Art? Audience? Sustainability? For Rain World, the cycle continues on.

Ron So is a writer, and so are you! Seriously, start a blog if you’re thinking about it. He also wants more people to play interactive fiction. Convince him Twitter’s worth using here.