Not a Hero, Just a Postman

Euan Brook explores Fallout’s mutating fantasies of power.

When you’re playing Fallout: New Vegas, it’s sometimes difficult to shake off the feeling that the entire game is poking fun at Fallout 3. One example is its emphasis on verisimilitude: Fallout 3 is sometimes criticised for the lack of resources found in the post-apocalyptic wasteland. How are these settlements surviving without any visible food or water sources, for instance? It’s a nitpick, but as the story is about saving Washington DC’s water supply it’s jarring that nobody seems that concerned about this important element of the plot. By comparison, New Vegas’s attention to minute detail borders on the absurd. Huge crop farms are dotted all over the map, long water pipelines travel from the Colorado River to the city, and electricity is produced by Hoover Dam. There are even outhouses on the outskirts of encampments, just in case you ever wondered about that.

That’s not the only subtle dig at Fallout 3. The popular Brotherhood of Steel faction, depicted in Fallout 3 as heroic Arthurian knights (with a literal boy-king Arthur in their ranks) are mocked in New Vegas as being pretend “Knights of Yore”, and shown to be immobilized by their obsessive devotion to their knightly codex. One character jokes about Fallout 3’s use of a giant robot at the end, saying, “And if you had, you know, a huge killer robot at your command. Yeah, that would just clutter things up. And a lesser person might want that kind of overwhelming force on their side but, you know, where’s the challenge in that?” There’s a character remarkably similar to a prominent character from Fallout 3 who is found dead, allowing players to pilfer and wear his popular sheriff costume. And one teaser trailer for New Vegas features a robot from Fallout 3 being shot while crossing the Mojave Desert. You can even find its remains in-game, repair it and later upgrade it—carrying real-life parallels to Fallout alumni Obsidian Entertainment improving upon Bethesda’s work.

Developed shortly after the series’ acquisition by Bethesda Softworks, Fallout 3 was the first Fallout title to be a first person shooter (FPS). Its use of Bethesda’s Gamebryo engine placed it in contrast with the previous Fallout games; Fallout and Fallout 2, as developed by Interplay and Black Isle, which used an isometric perspective that simulated the tabletop role-playing games (RPGs) experience. Playthroughs in Fallout and Fallout 2 are affected by a mix of player-character skill points and simulated dice rolls, which meant that the higher your character’s skill, the more likely they succeed in a given action. These include moves like fighting, sneaking around, lockpicking, computer hacking, and persuasion, which all play out in calculations of luck and character “skills”— the player’s input being the allotted character’s skill points.

The difference in perspective granted the player more power and control, rather than leaving it up to chance. The RPG design emphasizes diversity of play styles by giving equal weight to combat, stealth and diplomacy, whereas Fallout 3’s FPS style encourages combat to be used over other options. Lockpicking, computer hacking and stealth are still determined by the skill point system, but Fallout 3, as an FPS, gives the player more immediate control over their combat abilities, making it the likelier option when encountering a situation. Gunplay is more satisfying: it’s fast-paced, gory, and there are a ton of weapons with different effects to experiment with. Fallout 3 also introduced the Vault-Tec Targeting System (VATS), which allows players to view their attacks as slow motion cinematics. The enhanced combat is central to Fallout 3’s power fantasy, where satisfaction is gained through quick decision making (as opposed to the slow turn-based combat of the originals) and efficient resolutions are offered to problems through violence.

The power fantasy of Fallout 3 goes beyond gunplay, however. There’s a radio broadcaster who keeps a catalog of the player’s achievements, centering the game world around them by praising or condemning them for their actions. There are overt biblical connotations too; players witness the protagonist’s birth, and their father has plans to create an Eden in the wasteland. The protagonist is granted Messiah status by sacrificing themselves to bring about this paradise; inputting a code based on a passage from the Bible (Genesis 2:16) no less. And finally, the setting contains patriotic overtones. Fallout 3 is filled with the crumbling debris of national landmarks like the Washington Monument and Capitol Building, and quests revolve around repairing the Lincoln Memorial and finding the Declaration of Independence. There is an argument that the decayed appearance of DC is satirical, that the cartoonish fanaticism of the Enclave government, as heard in their radio broadcasts, caused America’s destruction. But the buildings can equally be seen as patriotic defiance, depicting an America that’s damaged but salvageable. The player is not just a hero; they’re an American hero. Fallout 3 is an overtly American experience in comparison to the desert world of the original games, which offers neither spectacular vistas nor recognizable American landmarks

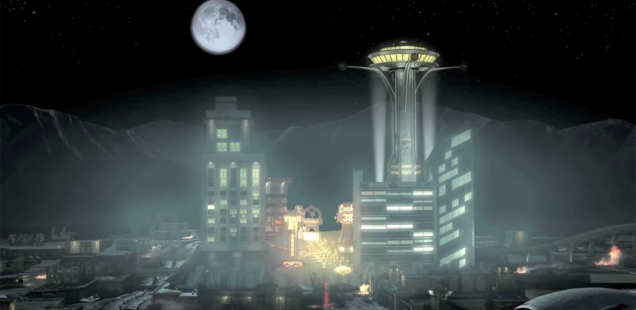

On a superficial level, New Vegas perpetuates this same power fantasy. It builds on its predecessor’s shooter fundamentals with iron sights and optional weapon modifications, and has even more options for cinematics with VATS and slowed down death animations upon achieving critical hits. The setting is equally devoted to Americana, differentiating its desert from the old Fallout titles’ with depictions of famous American sites like the I-15 highway, the Las Vegas Strip, and the Hoover Dam. New Vegas’s protagonist, the Courier, starts the game by being shot and left for dead, only to rise from the grave in a Messianic turn of events. While the original Fallout protagonists have always been subtly imbued with a sense of importance, their actions affecting entire regions of the post-apocalyptic wasteland, the first person perspective of Fallout 3 and New Vegas connects the player with this power in a more personal manner. The protagonists’ eyes are their eyes; they view both protagonists’ birth in Fallout 3 and resurrection in New Vegas in first person. This contrasts with the isometric perspective of the originals, which stage the protagonists as small chess pieces, visually no different from any of the game’s other characters. This detachment encourages roleplay, where the protagonist is understood to be a character controlled by the player, as opposed to the protagonist being an extension of the player in the first person titles.

What distinguishes New Vegas from Fallout 3 is how it complicates and comments upon the power fantasy that Fallout 3 relies upon so much for straightforward entertainment value. New Vegas introduces a hardcore mode to add realism to the gameplay: adding hunger, thirst and sleep meters for the player to constantly keep tabs on, as a crude recreation of eating, drinking and sleeping habits in real life, and ammunition is given weight whereas it had been weightless in Fallout 3. The Traits system from the original titles makes a return; these being character statistics that both improve and undermine the player’s abilities, such as “trigger discipline,” which permanently causes them to shoot more accurately but less rapidly. The verisimilitude of the game world’s design also reflects this change in the series’ power dynamics. Those water pipelines and farmlands, and the fact that every settlement has some explanation for how it’s supplied with water, become essential details when the player is constantly finding ways to quench their hunger and thirst. These needs don’t exactly make the game more fun, but they add an extra challenge that curb the player’s ability to dominate the game’s world, reminding them they exist within an environment that does not center around the player.

New Vegas’s overarching plot highlights its complicated relationship with power fantasy, while mining a dark vein of American mythology. Set in a frontier, the Mojave is a battleground between two invading factions keen to take control of the city of Vegas and the Hoover Dam, a valuable power source. The protagonist, known as The Courier, is granted kingmaker status, their actions able to break the stalemate and result in one faction’s domination of the region. At first the choice of which faction to stand with seems obvious: the New California Republic (NCR). Coming in from the West, they ostensibly bring order and democracy to the purportedly chaotic Mojave wasteland. They are even comparable to the Brotherhood of Steel in Fallout 3, who arrived at into Washington DC from the west to fend off the monsters and other dangers that plague the DC inhabitants. But as the player encounters the various inhabitants of the frontier, it increasingly becomes apparent that many locals resent the NCR’s encroaching presence. That the NCR are there for the dam has not slipped past their notice, so claims of liberation and democracy ring hollow. New Vegas is also the first game in the series to go in-depth about the complex narrative of war, and how the multiple perspectives complicate the binary narrative of good versus evil the previous games had worked within. Just because the NCR’s enemies – a fascistic cult who style themselves after Caesar’s Rome – are seemingly more morally corrupt than they are, that doesn’t make them the good guys. The player can revel in the violence of war, but there is no ending where a “just war” has been enacted. That’s why New Vegas stands in contrast to the wars waged against outright villains in Fallout, Fallout 2 and Fallout 3.

New Vegas’s reintroduction of the faction system, which affects how societies and organisations respond to the player, helps build this sense of power fantasy where the player is powerful but still limited in their influence. Help the NCR, and they take note of you as an ally. Perform enough violent actions against them, and they declare you a terrorist. Where Fallout 3 had designated safe houses and hostile battlegrounds, New Vegas’s attitudes are fluid, with these locations’ statuses defined by the player’s past deeds and aggressions. The story is changed constantly by multifaceted player choices that lead to a wide variety of outcomes. It is possible to bring the Brotherhood of Steel together with the NCR, but only if the player didn’t depose the Brotherhood’s old leader earlier, as the new leader is far more militant and anti-NCR. While the power fantasy of influencing the geopolitics of the wasteland is still present, it has increasingly limited and problematic options after every player choice.

This protagonist’s title is a deviation from previous games too. “The Courier” implies a strictly mercenary disposition, that the work being done is literally that: work. Whereas previous protagonists had lofty names like the Vault Dweller, the Chosen One and the Lone Wanderer, the Courier’s actions are always framed by this blue-collar title, their main quest simply being to retrieve and deliver a stolen package. They’re not a godsend, or a savior—just the postman. This is matched by the setting: Las Vegas is an infamously commercialist city that derives its power from its casinos and seedy reputation. The transcendent goals of the previous protagonists, saving the water supplies, creating a literal Eden with the Garden of Eden Creation Kit, tap into an old narrative of American mythology. Manifest Destiny, and picaresque heroes conquering the frontier wilderness and civilizing it for future generations even at the cost of their own exclusion. New Vegas is the Spaghetti Western cousin of these stories: the Courier’s goals are revenge on the man who shot them in the head, and personal enrichment. It’s the nakedly capitalistic version of the American Dream, removing the series’ pretensions of the player as “the good guy”.

New Vegas interrogates the heroism of the post-apocalyptic power fantasy. Where the morality of the previous games is uncomplicated, New Vegas’s moral compass is deliberately troublesome. Its gameplay has no romanticism; there’s no melodrama directing the player’s violence. You’re not killing people to save the vault or to find your father, you’re killing people for your own ends. For the sheer enjoyment of the power fantasy. New Vegas subverts the FPS genre with the reasons it gives the player for justifying their violence. Taking revenge on the man who shot you isn’t even required, but it is pretty satisfying, and it’s appropriately done in Vegas. After all, why do people go to that city? For pleasure, or greed. It’s the only American power fantasy that the game delivers: that you can actually get what you want in Vegas.

Euan Brook is a writer and reviewer in London. He likes rainy days, movies, and stories where the world ends at some point. Computer games have a lot of those stories. He begrudgingly uses Twitter.