Games of 2014 (7/15)

Our walk down memory lane continues with NaissanceE, The Long Dark, Eidolon, Secrets of Raetikon, and Hohokum.

NaissanceE

Games are unique in allowing us to experience space in an immediate and personal manner. Spaces which, similar to the wonders of books, are not bound by the conventional restraints of budget; the only limits, as they say, are those of the imagination. Mavros Sedeno’s first-person-walker NaissanceE offers one of the most original videogame spaces in recent memory: a sprawling environment of dreamlike, brutalist mega-architecture in stark monochrome, titanic structures, illuminated by wandering lights and ambient glows. It is a world of pure form at first glance; abysses of alabaster, giant landscapes of machinery and architectural detail, bottomless shafts, towering walls and dark, claustrophobic spaces of pure geometrical shapes.

And yet these delights of visual aesthetic are only the backdrop to the main attraction, a score comprised of various musical pieces by French and American avantgade musicians. The world of NaissanceE was actually built from scratch to accompany these ambient, abstract and weird soundscapes; the environments were designed to accompany the existing music, and to maximize and warp its effect in a perfect symbiosis of visuals and sound. Depressingly, NaissanceE insists on being a proper game by including puzzles and a handful of abominable platforming sequences bound to repel those come only to enjoy the view and bask in the atmosphere.

It’s tragic that these parts, existing only to anchor NaissanceE within the traditional confines of what it means to be a game, are acting as obstacles to a unique artistic experience. Some of these sequences are nail-bitingly tough, but should still be suffered through – or skipped with the help of the console – by anyone interested in what first-person-games can be. Because NaissanceE shines brightly nevertheless. The vistas it offers, the atmospheres it creates, the scenes it sets up for us are truly sights to behold, accompanied by a kind of music most players will never have heard before. One particular sequence stands out for me; like a dark twin to the bright abstraction of last year’s Antichamber, it pits its players in a dark, blurred sequence of disorienting déjà-vus and hallucinogenic disorientation, accompanied, of all things, by the eerie sounds of Pauline Oliveros’ avantgarde accordion piece. Please: Watch this.

NaissanceE must be considered a triumph for these glimpses of brilliance alone. Never mind its flaws: This is one extraordinary piece of capital-A Art.

Rainer Sigl is a carbon based lifeform mostly based in Vienna, Austria. He has been firing synapses to the tunes of videogames for a very long time.

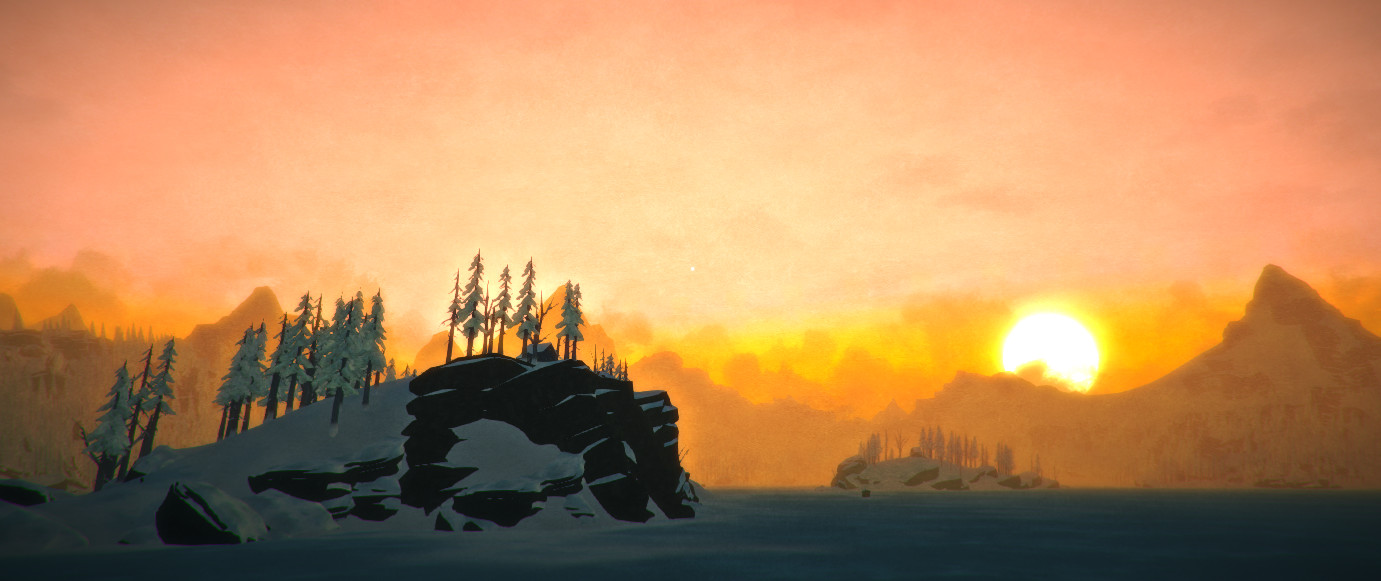

The Long Dark

The Long Dark is a game about survival.

You might get lost in the the beauty of the yellow sky when the sun quietly settles in the evening, shortly before you get lost in a snow storm. Then you’ll probably freeze. Maybe you find an empty house. But then you’ll starve. Maybe you find some canned beans or a chocolate bar. But then you’ll break your ankle while climbing a hill, and find yourself unable to walk and unable to escape the wolves that are closing in around you. Maybe you’ll find a gun and shoot them. Maybe you’ll live another day, but you’ll die eventually.

The empty homes and frozen bodies tell a story of a civilization that carved its mark into the wilderness just to be consumed by it again. What’s left are constant reminders that humans don’t have a place here anymore. You can gather resources, but they’re limited. You can hunt animals, but you’ll eventually run out of bullets. You can light a fire, but it’ll burn out. This place holds no future for you and nobody will be able to come back here to colonize it again.

There are no monsters in The Long Dark, there’s only a hostile world. It’s a slow and quiet game, but a restless one nontheless. Everything is in a constant state of decay. Your clothes are wearing, your food is rotting, your body is collapsing. Maybe The Long Dark is not a game about survival then, because you won’t survive. You can just try to escape the inevitable darkness for as long as you can.

Daniel Ziegener writes about videogames on the German sites herzteile and Superlevel. He also tweets a lot.

Eidolon

Eidolon

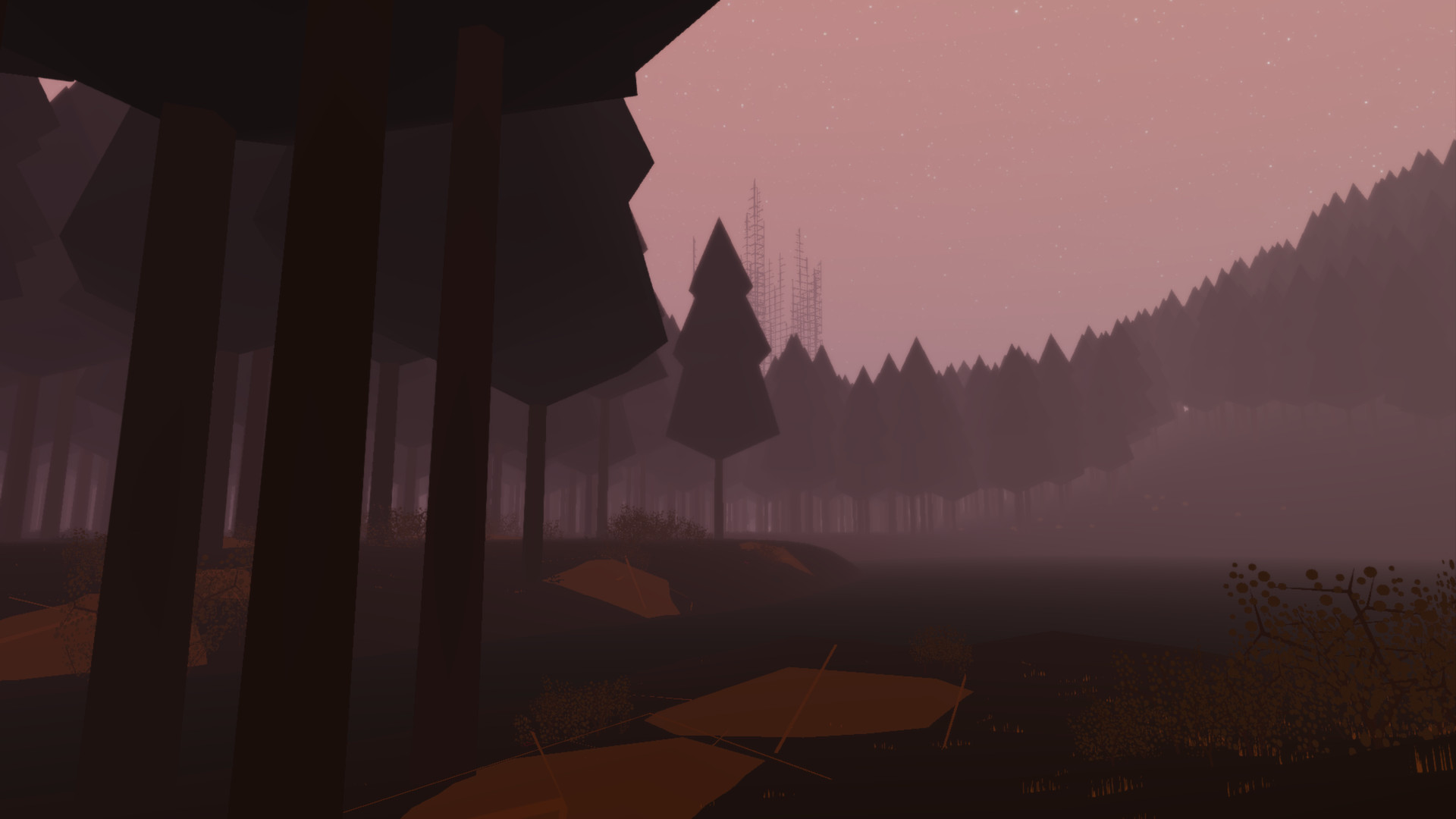

Invisible corpses permeate the vast emptiness of Eidolon’s post-human Washington State. Amidst a picturesque landscape of gentle contrasts and soft pastel, the echoes of humanity flicker in the distance. Floating a few feet above the ground, tiny cubes of light impart the stories of a people long gone. Captured in ornate, handwritten type, the dead grasp at immortality, their songs a cacophony of wishes and desires. Together, they weave a network of narrative excellence that is confident enough to cultivate its fragments as shadows of a larger whole.

Faded paper neatly folds into my notebook. Wanderlust lies close to the heart of Eidolon, but traversal alone fails to describe its sense of ghostly presence. Collecting the notes is a patient affair, strung together by bits of light floating in whatever direction the next note in a given narrative chain might be. In between, there is silence, occasional wild animals and light survival mechanics that control the pacing between gathering notes and scouring the countryside. Practically, it allows diversions of all kinds in a massive open space. If the trail runs cold and a narrative chain is completed, I have to rely on hand drawn maps and a simple compass.

‘I’ am hungry.

Freshly caught fish cooked at a tiny campsite beneath an infinity of stars makes for a nourishing meal. Binoculars close the distance and allow me to chart my route through the valleys. Of course, I had to acquire all of these items on my own. Eidolon is content to thrust players into its space sans any prior training, but does not prove too much of a challenge to unravel. The minimalist user interface will be specific enough to help, and obscure enough to foster an enduring sense of curiosity.

In contrast to the highly natural surroundings, the strange futuristic device you carry from the start is distinctly unfamiliar element and immediately subject to wild speculations about the boundaries and possibilities of Eidolon’s setting. Exploration and the exciting prospects of discovery mark every step of the quiet journey. Invisible corpses start walking in my mind and people come into being, conjured between the margins and lines of Ice Water Games’ stunning command of the written word.

The memory of human life is not quite extinguished: I find a road in the darkness and watch the sunrise, ablaze in orange and bright yellow. Chasing another light, the pale fog dissipates and I can see the bones of civilization break away and stretch towards the sky in a tangle of strange grids.

Philip Regenherz sincerely apologizes for the egregious theft of your time he perpetrated just moments ago. To claim much deserved vengeance, you may follow the evolving deterioration of his hopes and dreams on Twitter.

Secrets of Raetikon

Secrets of Raetikon begins with a bird falling from the sky into the arms of a giant tree atop a mountain. From there the player takes control of the bird and just flies and observes. Secrets of Raetikon cuts out all the fat and lets the player just experience the world around them, taking it in bits at a time.

It’s an excellent exercise in environmental storytelling, injecting just a few handfuls of human artifacts into an otherwise entirely natural, mystical landscape. It’s also excellent kinesthetically. To fly, the player must constantly flap their wings for a burst of speed, catch wind currents or nosedive to change direction; it just feels pleasant to move around the world, collecting beads along gracefully winding circuits. Imagine Ecco the Dolphin meets NiGHTS into Dreams.

Along the way are birds of prey and other predators tracking the defenseless player which, at first, really felt out of place. The only way you can defend yourself is by heaving a rock and flinging it at an attacker, or snagging them and dropping them into a lack or a bed of thorns, or by finding something smaller and more helpless and leading the predator to track that instead. After being tracked by a hawk for five minutes, it just becomes easier to lead it to a baby rabbit or a robin’s nest. The sharp squeal and crunching that accompanies an animal’s death really punctuates the gruesomeness of it. Maybe that’s the point: as liberating and beautiful as nature is, it can just as easily be cruel and horrible.

Secrets of Raetikon is simplicity done right: it’s movement and environment, with just enough interaction to make the whole thing meaningful. It trusts the player’s intuition to fly around with reckless abandon and to manage their own fight-or-flight responses when confronted with danger.

Mark Filipowich is the co-coordinator of the Blogs of the Round Table feature at Critical Distance and the curator for Good Games Writing. His worked has appeared in PopMatters, The Border House, The Ontological Geek and many other fine virtual games locales. He has a sweet blog called bigtallwords and he tweets irregularly and irreverently at @MarkFilipowich.

Hohokum

Hohokum, at first, entices you with its brilliant design and colors. It’s eye candy of the best kind: Each level – of which there are many, seemingly layered endlessly on top of one another – has been designed with a carefully selected color palette. While the color palette alone awakens the senses, the artwork is also quite good: it’s minimalistic, clean yet emotive, cute without being cutesy, youthful and merry without being childish or annoying.

But Hohokum is more than clever use of color schemes and visual design. Hohokum is also a playground. If you just want to move around these spaces, you can – the game allows you to take it in at this minimal, but no less important or meaningful level. If you want to interact with things, you can do that too – each level contains a kind of puzzle, frequently linked to an emergent narrative, that, when solved, alters that level’s environment in some way. Want to collect hidden objects across the levels in some way? If you prefer having a mission, this might be the option for you. Basically, Hohokum allows players of all types to have fun on the playground equipment.

What is most surprising, perhaps, is how simply and easily the game creates fun. The concepts of flow and ludic freedom are married seamlessly in Hohokum, and not just because those are the two main mechanics of the game: flowing serpentine motions and exploration. Hohokum, instead, manages to do so much with so very little. Hohokum is a reminder of what games can be when we step back from the complexity of what game can do, and remember what they should do.

Lindsey Joyce’s life goal is to get Hamlet on the Holodeck. In pursuit of that lofty end, she writes, edits, and works to finish her PhD in the field of interactive narrative systems. She is currently the Managing Editor for both Haywire and Five out of Ten Magazine. Her written work can be found at Critical Distance, Kill Screen, First Person Scholar and on her personal blog TheJoycean. You can follow her on Twitter.