2017: The Year of Puzzles

Jog your noggin with some fun brain-teasers: Gorogoa, Pan Pan, Puyo Puyo Pop, Opus Magnum and Crosscells.

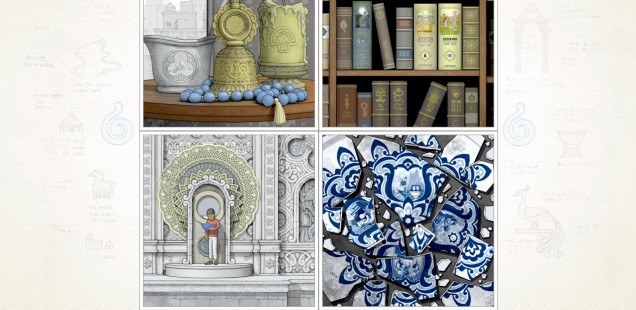

Gorogoa

Sifting through the layered panels of Gorogoa to find something of beauty and significance mirrors the search one must often undergo to find something as remarkable as this game in the Match-3-satured mobile store of your choice. Gorogoa’s 4×4 grid of image puzzles, all beautifully hand-drawn, are not something I’ve seen anywhere else. That alone grabbed my attention, and the feelings left by the journey that ensued linger.

People have asked me what Gorogoa is “about” and I struggle to tell them. There’s a boy, and he wants to encounter what I presume is the titular monster. For him, the journey is a straightforward path through doors and up and down ladders. For the player, it winds and twists through the lives of others familiar with the creature, ignoring limits of time and place. What they all have in common is this shared personal demon, something they’ve read about, known intimately or left in the past to be forgotten. Through the boy, they greet it together. There is darkness, and then a rush of colors. And there is tranquility for the player when pieces fit together just right, and a new door opens.

But more frequently, I tell them it’s a clever sliding puzzle game uniquely suited to mobile with gorgeous art, and that’s enough to go on. The Gorogoa, whether shared experience, feeling, or literal monster, tells the rest on its own.

Rebekah Valentine is a games, tech, and culture writer primarily based as an editor at App Trigger. She also writes about mobile games for GameZebo and shares a non-stop stream of Kirby pictures and video game food recipes on her Twitter.

Pan Pan

Pan Pan was one of the first games I had on my Switch and it sold me on the console’s potential. I could have spent brief windows of downtime going through Pan Pan on my phone, tapping to solve puzzles in its nice, pretty world. Instead, playing it on the Switch was the perfect fit. Relaxing on my couch with the portable but chunky screen, I immersed myself in Pan Pan‘s charming land. The puzzles are simple, the style is cute and the soundscape breathes real life into it.

But the thing I really loved about my time with Pan Pan was the quiet, wordless world that sat patiently and waited for me to come inhabit it. The game never prodded or pushed me into anything, it just dropped me in and then left me to my own devices. That kind of freedom was what gets me to step in and engage with it more than I often would with games that try to offer me more.

Pan Pan is a small game that called me to make more of it, and I loved what we made.

You can spot SuperBiasedMan’s rare microblogs over on Twitter.

Puyo Puyo Pop

Puyo Puyo Tetris is a joyous reminder of how important it is to continue to iterate on classic systems of play: in the places where it mashes its two games – Tetris and Puyo Puyo – together, it can feel a little strange, but the fundamentals of Puyo and Tetris are easily accessible, with the secrets of each of their separate universes contained within, ready to be mastered! And the combination of the two is incredible: Tetris gains so much from Puyo’s personality, and Puyo gets Tetris’s respect and reverence. As a player, I’m allowed to identify as a Tetris person, as a Puyo person, or as a hybrid of the two, and all of those identities are equally valid. This is also the first time I’ve ever played Tetris or Puyo competitively and it’s radically changed how I understand these simple puzzle games that I’ve grown up with my entire life.

I now understand what a fighting game is. Why we play fighting games. We do this because we want to show off cool moves that our friends don’t know and then yell at them when they beat us even though we worked really hard to master our T-spin and trailing setups. I thought I knew nothing about how Puyo Puyo worked and this game taught me that not only did I suck at Puyo Puyo, I learned I sucked at Tetris too! At the same time! That’s two for the price of one. That’s value!

This is the only game this year that I played both online and offline with friends, and that in and of itself is a hell of an accomplishment in 2017.

Solon is a nice kid who knows everything about the meditative art of Let’s Plays. Solon is a video producer, artist, and part time 7th grader. You can subscribe to the kid’s face on Youtube or talk to them on Twitter. If you are a big adult who needs production help done, you can email Solon’s face too! solonscott (a) gmail dot com

Opus Magnum

*CLONK* haunts my dreams. *CLONK* is failure made percussive, the sound of beautiful theory colliding with the hard limits of cruel reality. When I haven’t properly thought things through, or when my brain has failed to correctly account for the rotations, pivots and extrusion of my carefully-placed mechanical arms and reagents grind together, bringing intricate clockwork to a fatal halt, *CLONK* is my punishment.

Opus Magnum‘s puzzles are simple in concept: take reagents from a limited number of stacks, and manipulate them by arm, by track and by transformative glyph until they bond together to form the desired alchemical molecule. As in Zachtronics previous games, the process is an abstraction of programming, but where SpaceChem and Shenzhen I/O intimidated, the physicality of Opus Magnum‘s molecules lends clarity. When your mechanism fails, it’s plain to see where the failure occurred; when you succeed in crafting a working machine, your reward is to watch your solution wind its way through multiple iterations, before being scored across multiple – often conflicting – criteria.

There is no one, true solution. You build a working machine as best you can, using as many pieces as it takes – even if the result is a bloated monstrosity of tracks and wheels and pistons – and then it’s up to you: either take your success and move on, knowing that it’s good enough and that you’ve evaded *CLONK* this time, or dive back in and rebuild your machine smaller, faster, with fewer pieces, symmetrical in form or action, and watch it cycle endlessly towards clockwork perfection.

Rob Haines is a writer, programmer, and ex-turtle biologist. His work has appeared in Unwinnable Weekly, Kill Screen & Eurogamer, and his short fiction was featured in the BFS Award-shortlisted science fiction anthology Tales of Eve. You can find him on Twitter or at his blog.

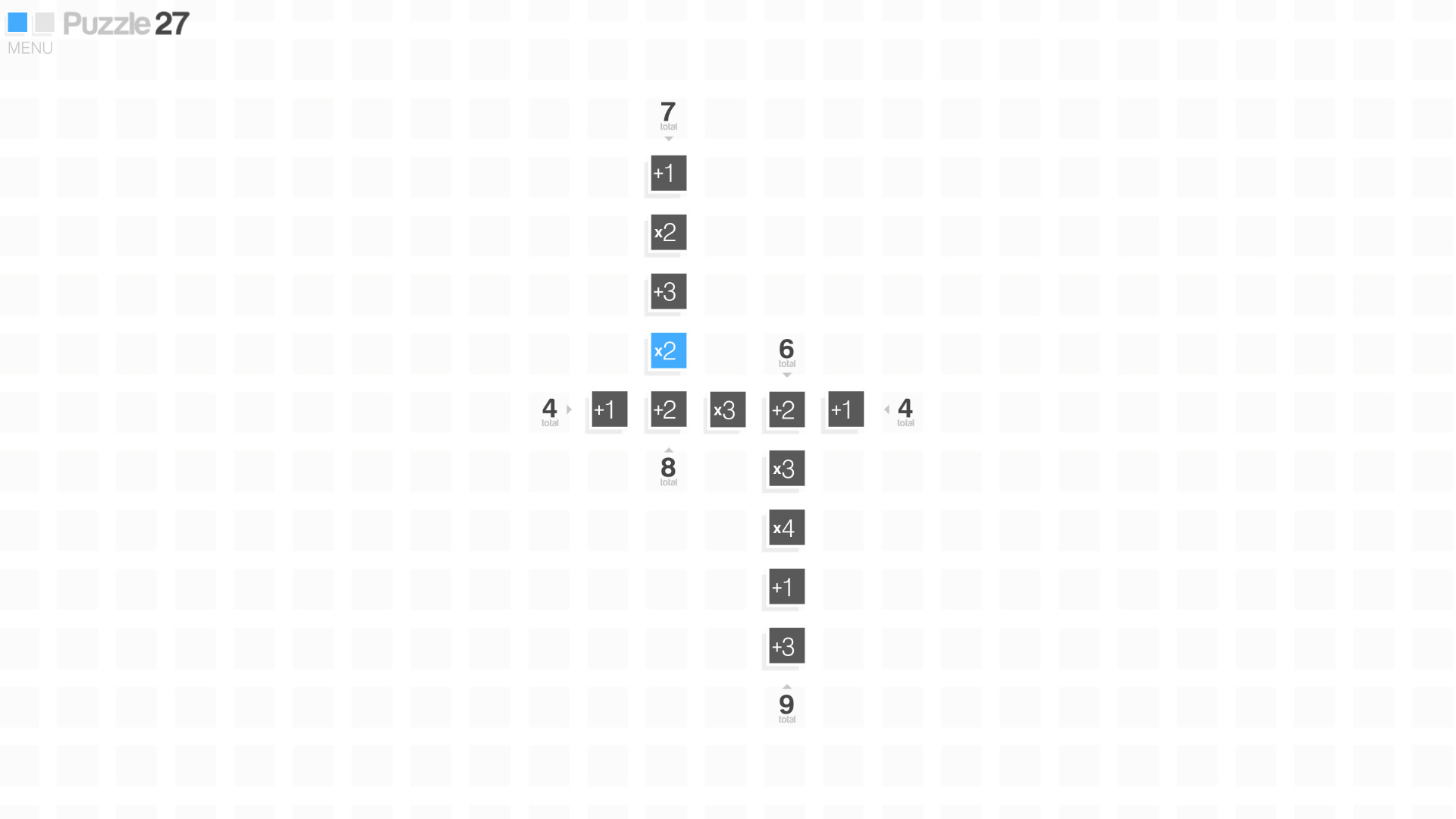

Crosscells

Crosscells is the latest game by Matthew Brown, following up on Squarecells and the three Hexcells games that came before it. The series plays like a mix between Minesweeper and Sudoku that the developer describes as an ambient logic puzzle game. In all honesty, this is my least favorite title in the series. It’s still fine, but for me the rule changes moving from Hexcells to Squarecells to Crosscells slowly eroded the charm of the series.

Hexcells had you finding the edges and poking them like you would a jigsaw puzzle, slowly revealing more of the layout as you go. With its immediate feedback and layering of new information, this was a game that clearly worked best on a PC. Now that Squarecells did away with the revealing of new information as you go and Crosscells did away with the feedback on mistakes, it feels like we reached a point where the game might be better off being played with paper and pencil.

So why did I even play it? Because of Hexcells Infinite‘s random puzzle generator. After playing hundreds of these procedural puzzles, they started to feel soulless. There was no human touch, no rhyme or rhythm to them. Despite the faults of the newer installments, they still give you that you that handcrafted Eureka moment as you progress through them, and Crosscells is no exception.

Ivo Pačnik never writes and is available on Twitter.