2017: The Year of Horror

Prepare yourself to be spooked by Bucket Detective, LOCALHOST, Tattletail, Where The Goats Are and Near Death.

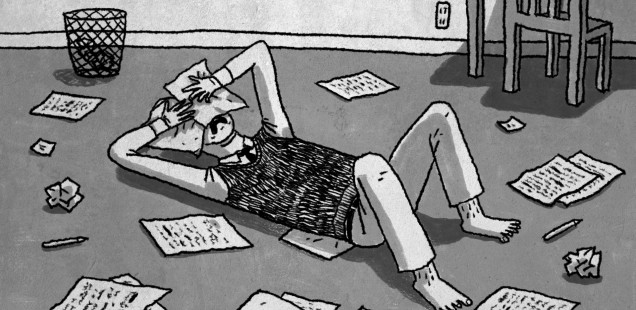

Bucket Detective

Many videogame protagonists are either heroic or flawed. Or both. But few are as bafflingly vacant as David Davids, who has made having kinky sex his lifelong goal. Through some leap of logic, it dawned upon him that being a writer would give him all the perverse sex he wanted. Women would be lining up in droves to bed him. The perfect solution! There was a slight kink in this plan though: he can’t write.

Fortunately, ‘twas a small problem that could be overcome by joining a cult. David decided to travel a few hundred miles to the cult’s headquarters, with hopes that it’ll imbue him with the writing finesse he so desperately needed.

At its onset, Bucket Detective is a hilarious little jaunt because of how half-baked David is; you can watch him commit to increasingly horrific deeds just to get laid. You may wince, laugh, or chortle uncomfortably at the absurd situations he willingly throws himself in. But set in David’s obliviousness and narcissism, the cult’s transgressions—from blind, unquestioning devotion to implied sexual abuse—are magnified. Turns out the real antagonist of this game is his hubris; he’s both too unsympathetic and obtuse to care. In light of the wave of sexual harassment revelations that took place last year, that can feel rather agonizing.

David’s vapid quest to get tons of sex may be amusing, but it also exposes his horrifying apathy. It’s also a timely reminder for us to be much less indifferent to the injustices that still persist today. After all, we can’t be as dumb as David, can we?

Khee Hoon Chan writes for Unwinnable and freelances wherever she can on the internet. She daydreams about being a professional Street Fighter player. Ask her about the weather on Twitter.

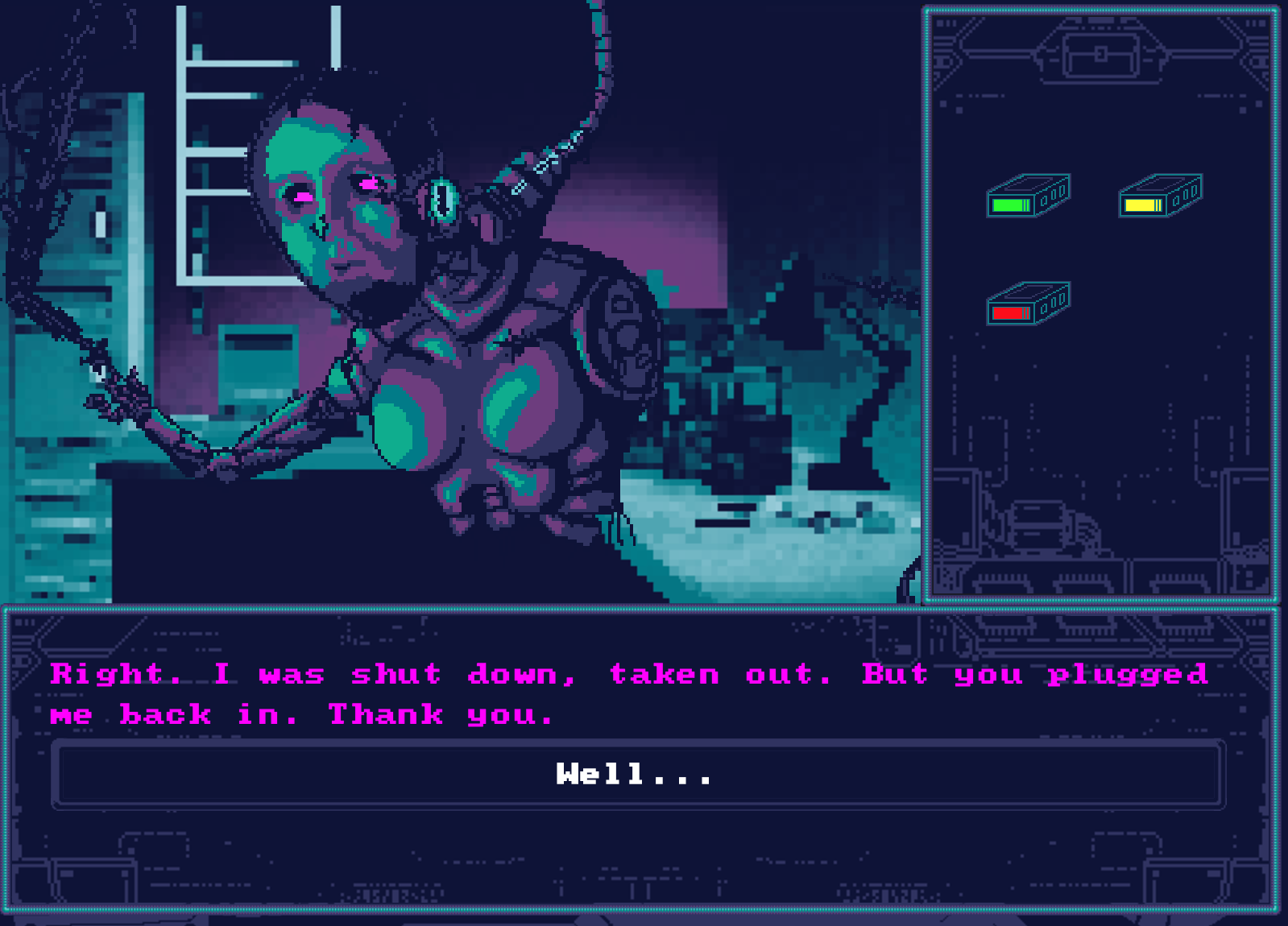

LOCALHOST

LOCALHOST, Sophia Park’s small game, oozes with great sci-fi atmosphere, due it’s electronic music, the well written dialogue, and the great animation, with its small variances. In a futuristic cyberpunk work, players are tasked with deleting drives that contain AIs, but to erase them, the player has to convince the four AIs to give access to the erase function. While I enjoyed the moral overtones of the story and the clever ways the dialogue creates clear distinctions between the AIs, the atmosphere of the game captured my imagination.

Right from start I became enthralled in this world – the moment I saw the decrepit robot, missing their left arm and lower-half, hung by their neck, I knew I was going to love this game. The screen is mostly tinted in blue and shaded with purple, except the eyes of the robot. Each time a drive is inserted, the eyes change in accordance to the drive’s color. Not only does the color change, but their behavior changes also, which is not only communicated through dialogue, but also through the way they physically manifest the robotic body – some feel at home, while others don’t take well to the body. The music also changes, yet still manages to remain atmospheric and a lot of the times chilling.

The atmospheric touches in the art and music serve to evoke the chilling existential themes of the narrative in abstract ways, creating a beautifully haunting game. These small details amounted to make one of my favorite games of the year. LOCALHOST left a deep impression on me, having sparked my imagination like very few games did in 2017.

Hussain Almahr is a writer and Anthropology student, he has written for Waypoint. When he’s not complaining about winter, he can be found tweeting and on his blog.

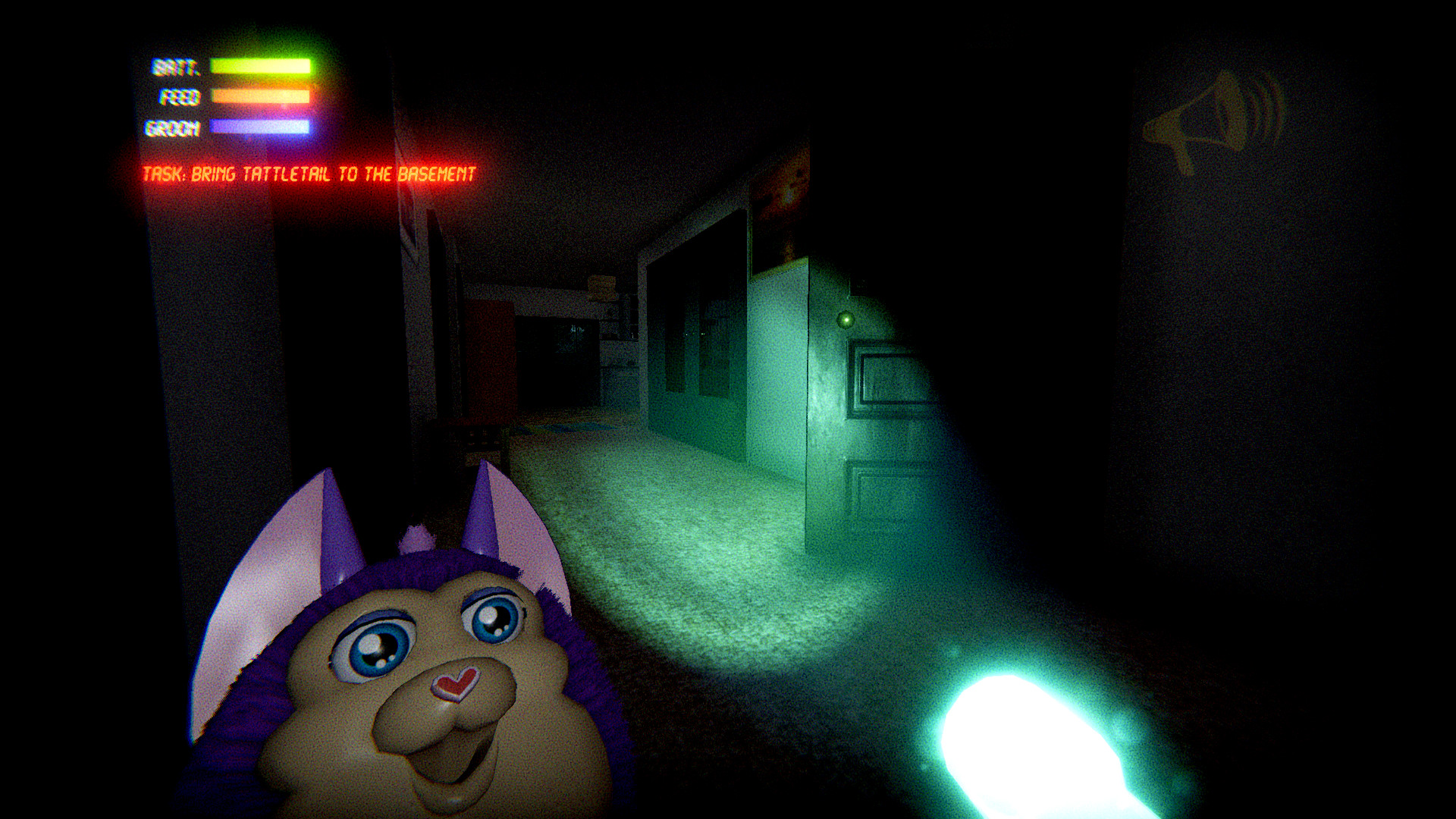

Tattletail

In the eighth episode of the podcast Important If True, Chris Remo, Jake Rodkin and Nick Breckon get to talking about a book called Alone Together. In that book, author Shelly Turkle observes a kindergarten class playing with Furbies. When one broke down, the children eagerly volunteered to “heal it,” to play doctor to this sick creature. But when their teachers pulled out scissors and pliers, the children became sick with worry. What if the Furby died? What if they couldn’t get its skin back on? Quickly, without help, the children conjured a terrifying supernatural scenario – the Furby’s furry skin was its “ghost” and its plastic form, filled with electronics, was a “goblin.” If they didn’t save the Furby, they’d be haunted by the ghost and goblin until they made things right. And so the children started to plan an exorcism.

In Waygetter Electronics’ Tattletail, you play a young child who must protect their Christmas present, a gurgly, giggly, battery-powered fur creature named Tattletail, from its furious and bloodthirsty Mama. It’s not a revolution – it’s still five nights of first person jump scares – but it’s really really good, a surreal late ‘90s urban legend. You clomp through your forced-perspective childhood home in the dead of night, trying not to tip Mama off by making any noise.

But you always do – the clacka-clacka-clacka of the glowstick flashlight, the heavy thuds of your feet on the wood, the tinny “I wuv you” soundbites that Tattletail might as well be screaming for how loud they are. These jagged lumps of sound, ripping through the silence. And then you hear her, the metal-on-metal whine that lets you know she’s here, and it crescendos to a dreadful quiet. And then her eyes, red lasers, on the other side of the basement. And you feel clumsy and desperate and you’re trying to fix this mess you’ve made but you can’t, you just can’t, and even though you’re playing this with five friends in a fully-lit lounge and you’re all in your late 20s you’re that scared little kid again, you’re never not that scared little kid.

Adam Goodall is a freelance writer, editor and legal publisher based in Wellington, New Zealand. He writes about New Zealand theater for The Pantograph Punch and about videogames, the internet and the justice sector elsewhere. You can follow him on Twitter if you’d like.

Where The Goats Are

When Hayao Miyazaki created Princess Mononoke, the historical fantasy film lauded as his magnum opus, environmentalism was clearly a major theme. The widespread desecration of the forest and the profane corruption of its guardians were due to industrialization – and of course, good ol’ human greed. Deformed by an iron bullet embedded in his heart, ugly tendrils slithered out of a forest god’s hide, leaving an indelible curse on anything it touched as it rampaged through a village. It’s a grotesque, uncomfortable sight.

But what can’t be seen can also be just as distressing. In Where The Goats Are, an old lady called Tikvah spends her days making wheels of cheese, milking her goats, and drawing water from a nearby well in a remote farm. She moves about in a slow and steady pace, tending to her affairs without much fuss, while a postman occasionally delivers her letters from her relatives in the city. Gradually, they take on a more sombre tone, as her loved ones share their experiences of urban isolation in the face of rising unemployment.

These scenarios aren’t depicted on-screen, however. You won’t see images of smog and pollution cloaking the sky. You won’t be witnessing the soulless exploitation of labor, as men and women alike marched away to towering factories before the crack of dawn. What you’ll see is Tikvah continuing to toil away, collecting eggs, watering her plants and making rudimentary sand art with a stick. Yet, the despair and melancholy will hit you just as intensely. I won’t spoil what happens at the end, but it’s something that stuck with me long after it’s over.

Khee Hoon Chan writes for Unwinnable and freelances wherever she can on the internet. She daydreams about being a professional Street Fighter player. Ask her about the weather on Twitter.

Near Death

“We were the only pulsating creatures in a dead world of ice” – Frederick Albert Cook on his North Pole expedition 1909.

There are not many places left on Earth where you can truly feel alone. One of them is Marie Byrd Land in West Antarctica, a gigantic landmass of permanently frozen barren rocks and ice, a windswept polar desert, still unclaimed by any sovereign nation. Now imagine yourself there, in the middle of a polar night, potentially lasting for many weeks, stranded in an abandoned research facility. The steel wands of the station squeal distressingly under the constant impact of a ferocious blizzard. The little light you have left is flickering and warmth is a rare commodity you learn to treasure above everything else. You are afraid of the permanent dark outside of the walls, of the loud noise of the blizzard, of the wind itself depriving you of every sense of orientation, of the cold. And yet, you know that the moment will come when you will have to leave this makeshift shelter if you want to survive for another day, searching the next building for some abandoned canned food, searching for water, searching for rescue. You will scavenge the few left over materials to patch up broken windows and to create a makeshift insulation for your parka, giving you valuable extra time, when – again – you have to leave another shelter for the next building

Near Death is a game about abandonment and desolation; it is a game about the absence of life, about the darkness and the cold that surrounds you. It is – so to speak – a simulation of loneliness. It leaves you the player accordingly alone, desperate and trapped in a hostile environment, looking for help in the deserted and partially dismantled Sutro station, a mere skeleton of a former human settlement. It excels in instilling the feeling of utmost abandonment. The game thus teaches you a precious lesson: that we should not fear outlandish monsters, not the foreign, nor the other, but rather exactly the opposite: the absence of others, emptiness and isolation.

Eugen Pfister is a historian teaching at the University of Vienna, specializing in the cultural studies of videogames. He has a blog and tweets at @Trogambouille.