2015: The Year of Interactive Fiction

Flip to page 83 to continue reading about Lifeline, Sorcery! 3, Sunless Sea, and We Know the Devil.

Lifeline

Every story is a time machine. This is true not just in the way story preserves information across time, and reinvigorates that information upon every (re)telling, but in the way story stretches and compresses the time it seeks to contain. Stretches of years can be reduced to a few moments. Instants can be drawn into hours of descriptive suspense. Characters onstage talk of dark and cold, and then claim first sight of the sun rising over the horizon and we are given to understand the long night they have spent on watch without being required to stand all that time with them.

We understand these things intuitively, after lifetimes of practice consuming stories. We comprehend a ten year war in an evening, a lifetime in 120 minutes. We step out of the stories and return to the real time of our everyday lives.

Dave Justus’s mobile text game Lifeline, however, does something a bit different. While the time-space of our stories is normally a discrete thing – starting when we sit down to watch, read, listen, or play, and ending when the story has exhausted itself or we decide to step away from it for a time – Lifeline starts and stops on its own schedule. It makes itself absent. It intrudes.

In a sense, Lifeline is an interstellar Robinson Crusoe story, but its genius is the recognition that contact is one of the necessities of survival. Like Taylor, we reach out through our devices, placing our words, our lives in other people’s hands. We are incomplete, inconvenient, and, we can hope, at times at least, utterly compelling. We never know when the line will go silent, or when it will spring unexpectedly, gloriously to life.

Gavin Craig is a writer and critic who lives outside of Washington, DC.

Sorcery! 3

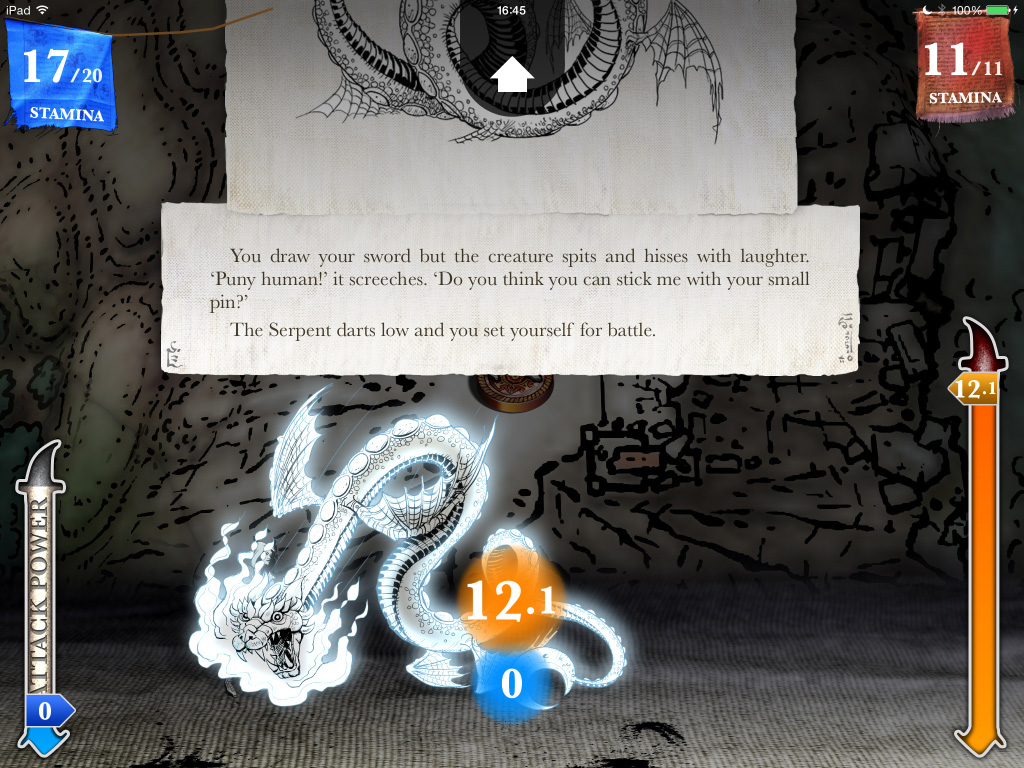

Writing about inkles’s Sorcery! 3 is like walking down memory lane. The game reminds me of my childhood in the early 90s when I used to read Steve Jackson’s gamebook series with friends during recess. With sharpened pencils and home-made dice – we carved them out of erasers – and all huddled in a corner, we discussed which decision would be best: casting a spell, throwing a pebble at the dragon, or running away? Back then the gamebooks from Steve Jackson, Ian Livingstone, and Joe Denver gave us, for thirty minutes each day, an opportunity to completely immerse ourselves in strange and fantastic worlds.

Playing Sorcery! games on my iPad was, in a sense, a homecoming to these fond memories, which was one of the reasons I bought it in the first place. And interestingly enough all three adaptions remained true to the genre by adapting and expanding upon it. Differing from Tinman Games’s “faithful” gamebook adaptions, inkle chooses to drop the dice-based combat, replacing it with a new decision-based system, and to open up the linear narrative to a kind of open world. By implementing new game mechanics such as time-distorting telescopes in Sorcery 3 and by migrating the narrative and decisions from text only to an enchanting map and cut-out characters, inkle has convincingly adapted the gamebook to digital media. Thus providing a perfect mis-en-scène for Jackson’s writing, which is not that strong at the macro level of the overarching narrative, but shines at the micro level of individual characters and encounters.

Who would have thought that Sorcery! 3, a work of interactive fiction on a handheld device, could be more immersive of an experience than many triple A RPGs? The only real qualm I have is that the third installment has become too focused on its open world and is, because of that, no longer suited for play during the little time I have on my daily commute.

Eugen Pfister is a historian teaching at the University of Vienna, specializing in the cultural studies of videogames. He has a blog and tweets at @Trogambouille.

Sunless Sea

What makes Sunless Sea work is the way it marries the mundane with the bizarre. The arc of the game is fairly straightforward: you acquire a ship, sail onto the titular zee, short for Unterzee, and make a living for yourself carrying cargo from one place to the next while managing supplies. Ultimately, you either retire to a life of luxury or die, leaving some portion of your wealth to an heir, who then sets out to zee and tries again. At its essence, Sunless Sea is a merchant marine simulator, but instead of moving, say, shipments of sugar across the Atlantic, you transport crates of human souls from Fallen London to the Tomb Colonies while evading enormous jellyfish and sailing across a vast underground ocean.

Along the way, you might stop to visit the Fathomking’s Hold, and trade a story of the Unterzee in hopes of gaining a boon from the great king of the Drownies. Maybe you will help unmake the massive basalt lion statues that loom out of the sea, carting sphinxstone back to London, one holdfull at a time. I would encourage you to avoid the Iron Republic, unless you want your port report to grow eyes and your shore leave to be more horrifying than relaxing. Coal is cheap there, though, what with its proximity to Hell, so if you find yourself low on fuel, perhaps it’s worth the risk?

Sunless Sea’s strange and wonderful creatures, stories and characters could easily have felt like they were trying too hard without the straightforward structure of the game’s mechanics. The game’s weirdness is magnified by the simple strategic questions about supplies and crew and morale, because these mundane questions make the game feel much more real. Anybody can write a story about weird people doing weird things, but without an anchor in the real world, these stories feel flighty and without consequence. Sunless Sea’s weirdness has weight because it feel like it happens to real people who have to make real decisions.

Bill Coberly is a law student and occasional writer-of-things based in Minneapolis, MN, where he lives with his wife and two small and snuggly terriers, Azathoth and Nyarlathotep. He founded The Ontological Geek, a website dedicated to games-criticism and cultural commentary, and you can follow him on Twitter, if you are so inclined.

We Know the Devil

Years of isolation and social indoctrination unspool in this brief visual novel about a Christian summer camp for bad children. Forced to spent the night in an abandoned cabin as punishment, three teenagers are told to protect themselves against the influences of an ever present, supposedly satanic presence. Slowly, they realize that the charms they have placed around the perimeter are not meant to keep something out. As it becomes impossible to deny their innermost desires, they become wary of the devil within.

Neptune is an ocean that seeps through every living being and strips them of their defenses, to rebuild them with an unrelenting warmth. She holds her smartphone like anchor and shield. Jupiter is a bright, golden storm that revolts against boundaries that have become dislodged in barely-contained guilt and fury. Venus never knew about the wings on her back, or where they might carry her, but as she begins to understand, she pulls from the depths within herself the courage to fly.

The three teenagers have never been permitted a common language with which to express their anguish; they disentangle the knots of far-right Christian conservatism and, with it, the suppression of their sexuality. These thoughts turn into conversations that are disarmingly honest and frequently undermine the authority and wisdom of adults, revealing the teenagers as people who might possess insight and emotional depth that have been extinguished in their older counterparts.

We Know the Devil surfaces the pairing-mechanics of dating sims: from scene to scene, players are asked to pair up two of the three teenagers, which will determine who hangs out with whom in the next scene; the wrinkle, of course, is that there will always be a third wheel. Making this choice does not just determine the content of the next scene, but the game’s varying conclusions. Is it possible to arrive at the end without one of them feeling excluded?

Philip Regenherz sincerely apologizes for the egregious theft of your time he perpetrated just moments ago. To claim much deserved vengeance, you may follow the evolving deterioration of his hopes and dreams on Twitter.