2015: The Year of Cities

Look who we happened to meet on the subway! It’s Off Peak, Mini Metro, Yakuza 5, Cities: Skylines, and Tonight You Die.

Off-Peak

Jazz cellist and game developer Cosmo D synthesizes two distinct spaces to set his subtly exhilarating, dreamlike game Off-Peak. We’re treated to a train station – a space governed by rigid, utilitarian schedules and fueled by unending commerce – that doubles as a museum and its underlying democratic ideal in making art publically accessible.

These tensions between the world of commerce and the world of art lie at the heart of Off-Peak, evoking the writings of absurdist author Franz Kafka in which individuals seem unable to topple vague oppressors in surreal worlds that resist interpretation. Off-Peak’s minimal first-person walker gameplay invites players to collect scattered pieces of a train ticket and thus carefully explore this surreal world.

Like Limits & Demonstrations or Thirty Flights of Loving, two other games partly about navigating a museum (and the latter also about a transportation hub), Off-Peak is concerned with our relation to art and cultural references embedded within its environment. Cosmo D provides a carnivalesque menagerie of characters and found objects carefully calibrated to stupefy and astonish. Culled together and exhibited for our contemplation include a colossal whale swimming through painted galaxies, a trio of bespectacled albino stalkers, giants playing board games, a serpentine Aztec relic, and real-life movie posters of the Polish school of design, including ones for movies The Legacy and Vertigo.

I think these Polish movie posters are the key text in unlocking Off-Peak. They come from artists conveying expressionist themes within an authoritarian world behind the Iron Curtain. Likewise, Off-Peak is about capitalism and its chokehold on both the creation and curation of art. Its setting overflows with displayed artworks, yet the musicians and artists you encounter admit to taking sabbaticals because such careers are not financially sustainable.

Perhaps such rarefied allusions will be lost to many, but at least Off-Peak engages with the kind of art that videogames rarely depict, asking players to consider a wealth of artistic and historical traditions difficult to ignore. Off-Peak is the rare kind of game that bridges videogames to broader discourses on art and its reception, and in so doing, moves the medium forward.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on Kill Screen, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, all of which are archived on his blog, Invalid Memory.

Mini Metro

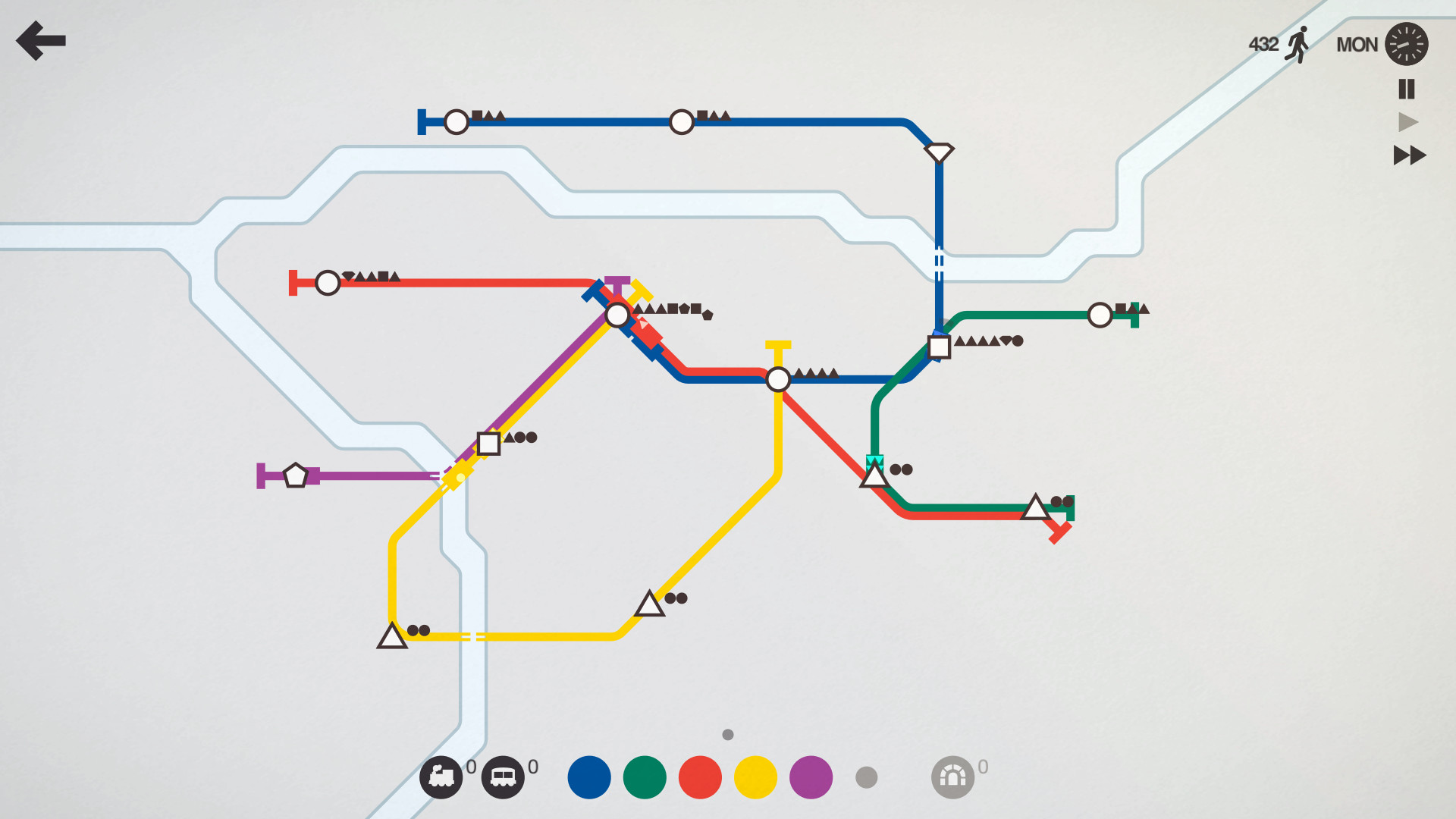

Mini Metro spent the best part of a year in Early Access, finally releasing in November of 2015. It’s half-way between a strategy game and a puzzle game, and puts you in charge of subway systems in various major cities across the world. Each game starts with three stations which you can connect together with subway lines and trains, with more stations popping up as you progress. Stations come in various shapes, and passengers will appear in the shape of the station they need to go to. New station types are also introduced as the game progresses. For every week of in-game time – about 2 minutes – you are given a new train and the choice of one of two bonus items, which come in the form of new lines, extra carriages and tunnels. These become crucial to keeping everything running efficiently.

The pace of the game is initially sedate, but as the speed at which passengers appear is constantly increasing, things get more and more frantic the longer you last, as you find yourself moving lines and trains around in order to desperately clear overcrowding at a station. As you become more familiar with the game’s systems, you’ll start surviving for longer as you develop strategies for streamlining your subway, and start noticing problems before they start. The different cities feature different layouts and come with subtly different tools: Tokyo’s Shinkansen moves much faster than other trains, for example. These differences, and changes you can make to the game mode help keep things fresh, even though you’re doing essentially the same thing every time. The visual and sound design are also notable. The clean underground map visuals work perfectly, and Disasterpeace’s generative soundtrack builds up a soundscape as your trains move around. Everything feels of a piece, and it’s the harmony of all these elements that makes the game so successful at what it does.

David Thatcher worked in the games industry as a QA technician for 10 years, and is now one half of the indie games studio TriCat Games, handling the majority of the art and audio tasks. His personal site is at giraffe.cat.

Yakuza 5

What makes Yakuza such a great series if you’ve never stepped into the shoes of Kazuma Kiryu before? As my Mom puts it, it’s that the games are “very Japanese”: Yakuza perfectly captures the day-to-day Japanese modern culture, and then wraps it up in the most gripping and entertaining Yakuza-based melodrama you could imagine. Yakuza 5 takes what makes the series great, and doubles down on it. The real standout are the sub-stories the main cast has. From driving taxis as Kazuma, to hunting game in the mountain as Taiga, these are fully-fledged quests and systems in and of themselves

Taxi driving is more entertaining than it has any right to be. Making sure the customers are happy by correctly indicating, slowing down smoothly and stopping at red lights, all while trying to keep up with their conversations and getting to the destination on time is a delightful challenge. These missions have the added benefit of levelling up your taxi to unlock decals, engine enhancements and sick rims allow you to take on the Devil Killers, a renegade group of engine-heads that are terrorizing the city in a high-speed Daytona/Ridge Racer-esque race.

You can find the same attention to detail at every corner of Yakuza 5. A stop at Club SEGA presents you not only with a playable Taiko no Tatsujin – a debut for this rhythm game outside of Japan – and an arcade version of Virtua Fighter 2, but also PuriKura photo booths and a multitude of crane games filled with Hatsune Miku figurines and cute plushies. This is only the tip of the minigame iceberg. This is only in one building. One location in one city, of five. You’ve yet to experience the ramen minigame, the shogi and mahjong leagues, the underground gambling area, pachinko parlours, darts, all the pool variants you can possibly think of – the list goes on. A literal checklist in the pause menu that tracks everything you can possibly do, mind.

Don’t be surprised if you don’t even reach 40% of game completion by the time the final act falls. The main story is only a small part of that percentage. And you’ll come back after it’s all over, just to breathe in that virtual Japanese air once again and experience something that you’ll never get anywhere else.

Andy Rae is a mythical sloth-like beast that can be rarely sighted in Leeds, UK. When he’s not in his natural sleeping state, he can be found talking about anime on the Key Frames podcast. The best way to capture this elusive creature is to place an amiibo under a box propped up by a stick.

Cities: Skylines

At some point in each of my Cities: Skylines games I rename a neighborhood “Poop Plague Memorial Heights.” This is because, at the same point in each game, something goes mysteriously wrong with my plumbing and everyone dies from sewage-related illness. The trash and bodies pile up, their removal hindered by my poorly-laid roads, and there’s a bit of a scramble until I can right things again.

I’ve come to accept this as part of the rise and fall of my cities. Like a well-functioning water system, the game has an ebb and flow; there are problems and solutions and problems again. There’s something delightful in figuring out where a situation originates – be it a lack of workers, a traffic snarl, or low property value – and righting it, only for the fix to ripple out into new, unexpected waves. Change an intersection, and green smiles and red frowns flicker across your city like a switchboard: there’s better traffic but more noise; the rich part of town lost their park but can get to work easier. It’s a gentle pull and tug, one that can go from soothing to demanding in an instant, but one that is always captivating.

Certain values implicit in the system can feel constraining at times, and the fact that all my citizens are white and most of them are blond gives me pause. But Cities: Skylines is a game about cities rather than people, about tinkering with roadways and zoning laws and seeing what happens. The sound design and colors make clear that the game is a big toy, and each new start is like emptying a box of Legos onto the carpet as a kid and spending hours lost in your imagination.

Riley MacLeod is the Managing Editor of Kotaku. His work has appeared at Offworld, Kill Screen, Unwinnable, Zam, and others.

Tonight You Die

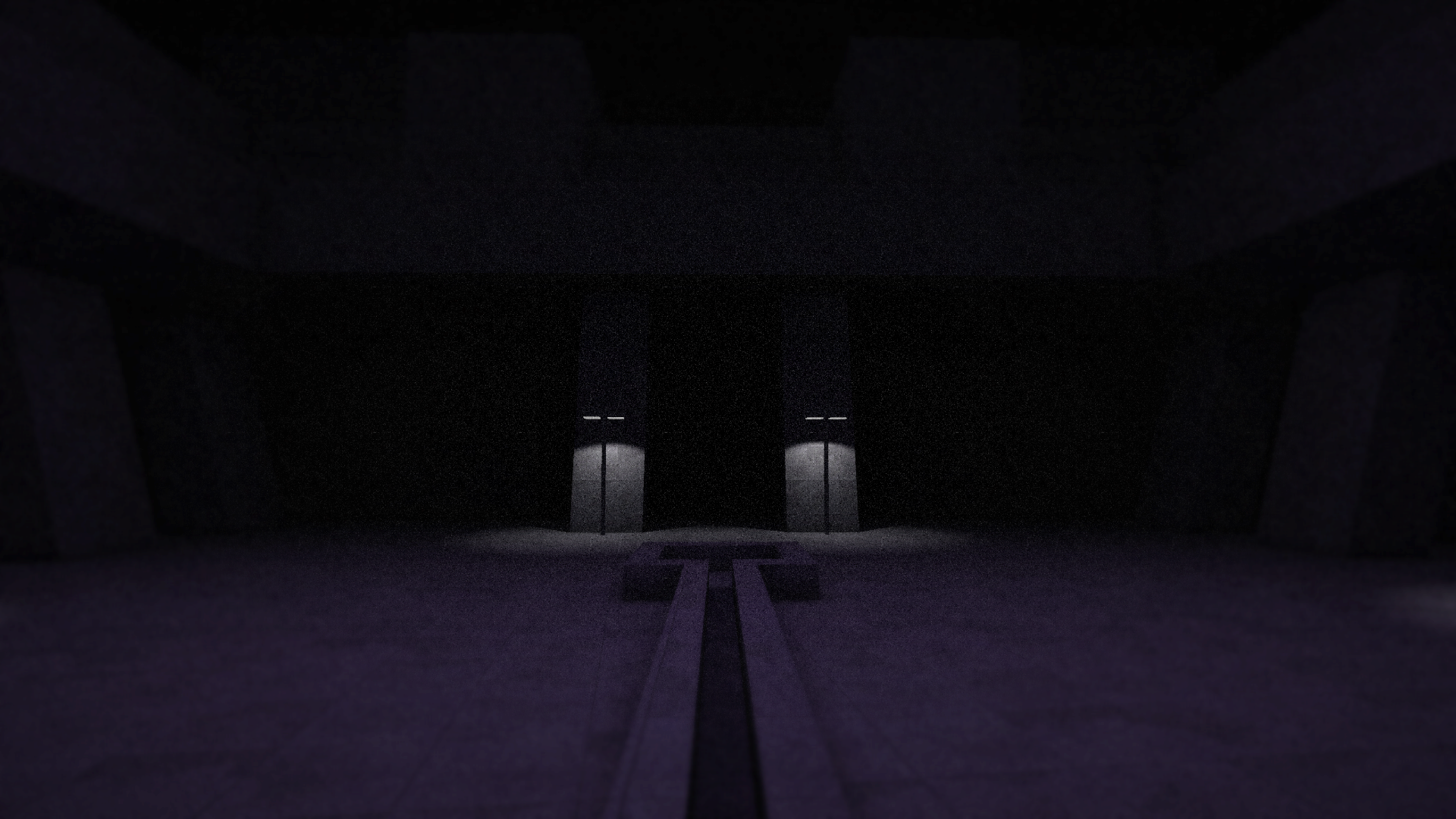

I played Tonight You Die by Duende Games sometime during the summer of 2015; I played through it once and haven’t touched it since, for it is a game that I don’t want to experience twice.

It started like most other videogames do: By showing me its title shortly before you’re allowed to take control over your character and explore the space around you. However Tonight You Die isn’t only the game’s title. It’s the only form of exposition it gave me. Neither did I know who I was, nor why I was walking around a seemingly abandoned city at night. All I knew was that at some point, something will happen that is going to end my existence.

This sense of foreboding, combined with the uncertainty about what exactly it is that was threatening my life, turned what at first appeared to be a simple first person exploration game, into a full on mental assault. I can’t say that I actually explored the space that Tonight You Die created for me. To me it felt more like an escape, even though I had no idea where to go. At no point did I feel safe; never did I think that there might be a way for me to release some of the pressure that was constantly building up in my chest.

It’s a bit unusual to use the phrase “I was glad when it was over” in a positive context, but I was indeed glad when I was done playing Tonight You Die. From the abstract ugliness of its city, to the constantly growing noise of its soundtrack: It felt like the game didn’t want me to exist. The fact that Tonight You Die communicates most of its ideas just by means of sound and space stood out the most for me. It’s a great demonstration of how much you can accomplish just with spatial design and it’s games like this that make me the most excited about the future of this medium.

Eric Merz spends most of his time making a videogame of his own. In fact, he should finally come up with a name for it. He does have a Twitter account and you can play his games on itch.io. He also occasionally writes about experimental games in German and used to be quite active on YouTube.