Opened World: Metafictional Warfare

Miguel Penabella sees the abstractness of modern war reflected in Black Ops III.

Of the three primary studios that develop games for the Call of Duty franchise, Treyarch’s Black Ops series is consistently the wildest, with its speculative, paranoiac fiction. These games’ storylines cut to the heart of our contemporary unease with governmental bodies and the militaries that support them. Treyarch’s latest entry, Call of Duty: Black Ops III, also boasts the most fragmentary narrative, jumping back and forth across timelines and shifting through layers of reality. Crucial exposition is casually dumped in an in-game database accessed between missions—pages and pages of sprawling text are navigated via hyperlinks, like a non-linear Twine game. This confusing, convoluted means of plotting denies straightforward exposition, and the campaign is thus total abstraction. The story centers on neural technology that allows characters to enter virtual spaces that represent the inner workings of the mind, melding wakefulness with dream. In these fabricated spaces, characters lose track of what is real or simulation.

This concern with warfare becoming increasingly abstracted, executed by proxy via drones and virtual programs, exists in military practice today. Black Ops III often borders on the intangible and avant-garde, but only because warfare has evolved so rapidly that it seems unreal and fictional. Soldiers and terrorists hacking into and controlling armed robots is not merely action spectacle, but a fearful reality. Evoking the language of videogames, the real human targets of drone warfare are marked and dehumanized as “objectives.” Data is compiled for self-learning algorithms to react more quickly on the battlefield. Such technological developments suggest a modern war zone that is no longer recognizable as a straightforward conflict between human bodies; experimental media and mechanics have obfuscated once clearer lines in the battleground. Black Ops III responds to this changing face of the military, directing conflict inward towards a cognitive battlefield that allegorizes these new digital front lines. Gone are the transnational campaigns across borders and against specific countries and military bodies, instead pitting the player against more obscure entities often left unseen and potentially nonexistent. By setting sequences in the simulated space created by the player-character’s direct neural interface (DNI), the game interiorizes its action and thus renders it suspect as scenes are filtered through the haziness of memory, trauma, grief, and mental breakdown.

Black Ops III presents not only a conflict of internal struggle, but also self-critique. The game aggressively questions the can-do heroism of previous Call of Duty games, presenting an environment that is already utterly devastated regardless of the efforts of the player. Indeed, some have written cogently about how the disastrous consequences of climate change undercut the power fantasy of a single person saving the world. If guns and knives cannot reverse irreparable damage, then the game suggests that the conflict is already lost, and that action sequences are merely survived rather than won. When a tsunami rolls into a ruined Singapore, players can only anchor in place and not retaliate. Black Ops III’s backdrop of climate change, surveillance, exploitative corporatism, and technophobia presents complex issues that can only be effectively addressed with diplomacy and shared cooperation among nations, a language with which the action-oriented Call of Duty series is not equipped. Moreover, the game casts doubt on organizations such as the CIA given repeated ideological and moral failings, a refreshing counterargument voiced by Justin Keever for Paste against the typically pro-American reading of the Call of Duty series. If these games represent a “pop-culture prism through which we see and express our relationship with war and other geopolitical anxieties,” as critics like Emanuel Maiberg argue, then Call of Duty speaks to our relationship with videogames and the culture surrounding them as well.

The game investigates not just contemporary warfare and technological advancement, but also how videogames themselves operate and position the player in a narrative. Within the first half-hour of the game, the “New World” level finds the player-character in a medically-induced coma after being critically injured by an enemy robot. The aforementioned DNI allows the player-character to enter a dreamlike space within their subconscious, what Commander John Taylor describes as “a simulation inside our minds,” thus linking these sequences afforded by the DNI to videogames. Indeed, the logic of these virtual worlds follows the imaginary logic of games, in which action can be paused and images distort and glitch as though reality is written in code. The DNI thus represents a game-within-a-game: we control the player-character controlling their own self-image within their mind.

Much like an episode of Black Mirror, these DNI sequences explore the dilemmas created when human memories coalesce with data and can no longer be distinguished from real events. By setting entire sequences in these virtual domains, Black Ops III reflects a world where prototype technologies develop at a pace faster that we have time to process the consequences. A growing sense of unreality emerges when the geopolitical landscape is too difficult to comprehend, especially when the mechanisms of the military-industrial complex remain secretive and seem like science-fiction. Controlling drones and fighting in the virtual space of the DNI recalls the targeted killing of the “Death From Above” mission in Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, in which players interface with a battlefield from behind an infrared surveillance screen. Here, technology serves to distance us from reality, in which emotionless commands from an unseen authority declare “Light em up” and “You got him,” while the player-character drops bombs on pixelated targets from afar. The sequence emphasizes this disconnect via its stark visual fidelity to the lossy infrared feed that presages the chilling airstrike footage leaked by Chelsea Manning at the height of the Iraq War. Modern Warfare presents the harsh truth of asymmetrical warfare: the physical displacement of the aggressor miles away from a human target abstracts and declaws the immediate brutality of warfighting to make killing palatable. Black Ops III similarly suggests that warfare’s increasing complexity has a traumatizing effect, as characters’ mindsets deteriorate over the course of the game as they fail to grip a constantly changing reality and suppress disturbing events too difficult to bear.

In modern military practice, virtual reality can serve to offset this trauma, once again tethering the battlefield experience to complex technologies that obfuscate warfare. In Harun Farocki’s documentary Serious Games III: Immersion, the filmmaker explores the use of videogames and virtual reality as a tool for the military. Specially designed programs that simulate a nondescript Middle Eastern battlefield offer soldiers suffering from PTSD a way to relive traumatic experiences for the purposes of talk therapy and rehabilitation. However, this technology operates not as a means to facilitate the healthy transition of soldiers returning to civilian life, but as a way to more quickly alleviate trauma so that soldiers can re-enter combat and thus maintain a well-oiled war machine.

Black Ops III’s DNI functions similarly, since the “New World” level serves both as a virtual tutorial for the player-character’s bio-augmentations and as a therapeutic tool to address trauma. For instance, when a robot ambush reminds the protagonist of the events that led to their coma and ensuing virtual experiences, the game stutters between a first-person and cutscene perspective. This unexpected shift emphasizes how their grasp on reality and perspective has been undermined by prior events and how the DNI technology has unanchored the protagonist from a concrete state of being. Players should suddenly feel cautious embodying a character who can’t distinguish between realities, where rogue memories come crashing into the virtual space of the DNI. Indeed, real-life neural interface researchers have encountered the problem of invasive brain spyware and malware that extracts information from neural signals, allowing malicious users to hijack and alter the components of a neural interface in use. Here, the threat of neural malfunction calls into question the reliability of memory itself. Internal trauma or external manipulation can undetectably distort the key frames we use to make sense of the world, and the game portrays the increasingly alienating battlefield through a lens of unreliable narration.

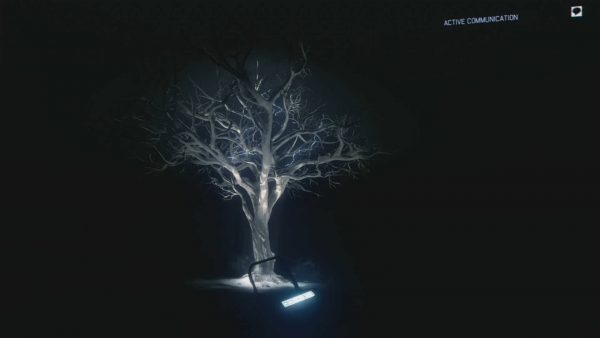

An overarching sense of distrust and falsity looms throughout the game. For instance, the DNI allows other characters to secretly listen in on seemingly private conversations over its communications network. The player-character’s paranoia over the loyalty of squad members Taylor, Hendricks, and Rachel Kane reflects a growing distrust of reality as the DNI steadily becomes corrupted over time. At one point, Taylor speaks to the player-character over the network even though they’ve ostensibly gone off the grid. This solipsistic voice in one’s head gives players a nagging suspicion of the characters’ grasp on reality, especially when such fallacies are casually brushed off. The standout mission “Demon Within” provides the most self-referential sequence this series has produced, calling attention to the artificiality of its world and visualizing a collapsing reality. Here, the protagonist interfaces with the dying soldier Sarah Hall’s DNI to access her memories, projecting us into an abstract mental space. Images such as a ghostly tree crackling with electricity in a pitch-black void and memories given form as islands that break apart and rebuild evoke a dreamlike quality, a description that Hall echoes as she guides the player through her subconscious.

The “Demon Within” sequence unearths the truth behind the game’s central conspiracy of a deadly CIA black project. Revealing this truth requires a journey through earlier memories, and the player must fight enemies that act like defense mechanisms preventing access to repressed trauma. The human brain serves as a site of horror; reality is skewed out of focus, obscuring the player’s eyes with a sanitized view of warfare typical of older Call of Duty games. Sarah Hall delays access to the CIA conspiracy by instead guiding us through the Battle of Bastogne, a World War II conflict that she researched as part of her training. The player-character experiences Bastogne through Hall’s mind, perceiving a 1944 event as a person living in 2065. Futuristic weapons anachronistically appear in this WWII setting and action unfolds in reverse. Hall sees the battle as indicative of bravery and courage, values that have been imposed by secondhand media like Call of Duty games that turn warfare into entertainment. Her unreliable account of the battle and insistence that it was a noble campaign shrouds its devastating reality. An external search of firsthand accounts note “strips of skin” that hang from trees, the winter cold that makes breathing feel “as if our lungs are full of ground glass,” and wounded and dead soldiers that resemble “a shapeless mass of crushed flesh.”

The game’s version of the Battle of Bastogne derive not just from Hall’s memories, but also from the collective memory of videogame audiences who are familiar with previous Call of Duty games set in World War II. The sequence involves a sprawling, desperate battle where players charge toward enemy lines with a squadron of other faceless soldiers, dodging a torrent of grenades lobbed in every direction as though we’re back in World at War. The shift in gameplay style is jarring, considering most of Black Ops III consists of restrained skirmishes accompanied only with Hendricks and not an entire military front. Guns use old iron sights, but because this is only a false memory of Bastogne, the protagonist can still boost around with a jetpack, deploy bionic abilities, and activate tactical viewpoints against soldiers ostensibly from the past. The music in this level also invokes players’ memory of older titles, eschewing the rest of the game’s glitchy electronic score in favor of a markedly throwback orchestral track that interpolates elements of the bombastic, unironically heroic main theme for Treyarch’s Call of Duty 3. The sequence blends aspects of past and present Call of Duty, and like the disordered reality of the player-character, it calls attention to the fakeness of this world and acknowledges how this series as a whole has peddled ahistorical, bloodless simulation. Collectibles can be found in the virtual space of “Demon Within” and brought back to the protagonist’s bunker in the ostensibly “real” world. These little details should tip players off that the entire reality of this game is suspect even after the protagonist exits the virtual space of the DNI, signaling a broader mental collapse.

By distorting the look and feel of Call of Duty games, Black Ops III more closely resembles the abstraction of warfare as it exists in our current moment, in which reality itself seems like a work of fiction. The game describes the DNI interface as “an immersion experienced with Sarah Hall,” a description that sounds more like a videogame than a piece of speculative technology. Nevertheless, our current geopolitical landscape increasingly entwines the mechanisms of games with that of the military, in which drones are piloted from a distance and warfare is fought asymmetrically on a screen. Black Ops III may not be the most subtle or elegant commentary on the gamification of warfare or bodily augmentation, but it’s as provocative and effective as a Paul Verhoeven film like RoboCop. In the game’s last mission, “Life,” Hendricks explains that the cryptically named Frozen Forest they’ve been chasing after is merely a codename for a digital afterlife crafted by a rogue artificial intelligence. With the aid of the DNI, human consciousness can live on after death via simulation, but the protagonist desperately asserts that it’s all an illusion. When technological advancement results in a world where data becomes interchangeable with consciousness, the human element functions as the ghost in the machine. With videogames, the player controlling the onscreen avatar serves as that ghost, the consciousness that animates the digital self via a controller. Similarly, as warfare turns to unmanned vehicles and anonymous drones to settle conflicts on a virtual plane, one can’t help but think of the actual human beings that nonetheless undergird these conflicts. At what point do we lose sight of the lives at stake, especially when they’re rendered as 1s and 0s on a screen or abstracted beyond recognition completely?

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.