Opened World: Let’s Eat Capitalists

Making a burger can be a rallying cry for action.

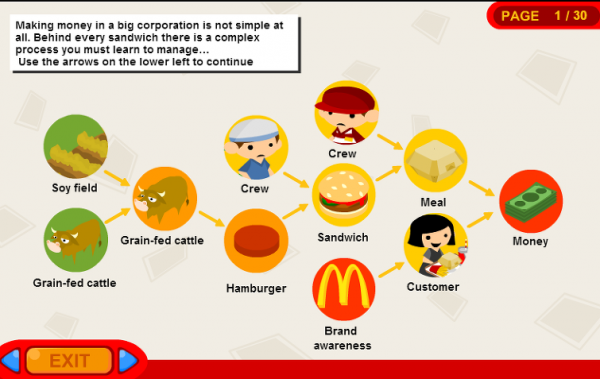

How can videogames effectively critique a wider media culture and broader industrial concerns? As critics steadily adopt a more analytical and politicized lens with which to examine games, how can the games themselves critique real-world phenomena and issues like globalization, corporatism, and the displacement of peoples? Writers and academics like Lana Polansky and Ian Bogost have certainly covered how games can be politically and socially deployed, and what will be crucial in this critical conversation are the deeper industrial issues that undergird all videogame texts. Taking Molleindustria’s 2006 release McDonald’s Videogame as a point of reference, we can breakdown its strategy of critiquing McDonald’s on multiple fronts as a way to identify productive ways that games can critique industry concerns. The game adopts the political values of Molleindustria founder and Carnegie Mellon University professor Paolo Pedercini, conveying a left-wing, activist urgency to tackle themes of labor and exploitation. Players roleplay as the CEO of the company and manage four key sectors: cultivation (of raw materials), production (of beef), transaction (of burgers), and reception (of the McDonald’s brand). By addressing these multiple fronts that comprise the total industry, McDonald’s Videogame targets McDonald’s to makes the broader argument that corporations sustain themselves via processes of systemic oppression and corruption, affecting not only the health and bodies of individual people, but also world economies and the environment.

McDonald’s Videogame condemns the titular fast food company from a Marxist perspective, as well as business simulation and tycoon games. These types of games perpetuate corporate ideologies and abstract complex issues like the extraction of material resources, the exploitation of workers, and the destruction of the environment as a source of unquestioning “fun.” There is no end goal to the game, suggesting that this genre of games (and corporatism in general) has always been about the perpetuity of making money. To generate revenue, players will have to make unethical choices such as bribing public officials to quell fast food workers’ strikes, genetically modifying soy products to feed beef cattle, launching misleading advertising campaigns, and displacing indigenous peoples off their land. Pedercini specifically designates the game as a parody meant for educational purposes and—according to the game’s website—as “an anti-advergame for the fast food industry.” Advergames refer to games purposefully and exclusively designed to promote a branded product, political campaign, military body, etc., such as Burger King’s mascot-starring Sneak King or the U.S. military’s recruitment tool America’s Army. McDonald’s Videogame satirizes this genre, offering a broader commentary on videogames’ entanglement with neoliberalism, globalization, and free enterprise.

On the level of agrarian cultivation, Pedercini links American corporate development in foreign countries with a longer history of colonial expropriation, facetiously remarking in the tutorial, “Obviously you have to conquer your land as our forefathers did.” Players raise soy crops and cattle ranches near the fictional South American coastal town Sao Josè. Over-development inevitably leads to clashes with the local government, but the governor of Sao Josè can be bribed so that common land originally used to grow food for local residents can be bulldozed to make way for McDonald’s to cultivate. According to the tutorial, this seizure of land will “bring richness to this corner of the world,” cynically taking jabs at trickle-down economics and neocolonialist efforts by Western corporations to expropriate the resources of South American countries like the banana republics of the past. Moreover, players can destroy the rainforests and indigenous homes that border Sao Josè, suggesting not only the displacement of peoples deemed “disposable” by corporate development, but also that the environment itself is negligible and must be conquered under the name of capitalist growth. Soy fields can be genetically modified with more aggressive pesticides, and cattle can overgraze the land, thus severely compromising the fertility of once green pastures after years of heavy development. If crops are not micromanaged and rotated with the seasons, land can become arid and un-farmable, gesturing towards the slow violence of environmental decay over time. All these neocolonialist strategies of wealth extraction—the exportation of pollution, the seizure of local land, the corruption of Latin American governments, and the destruction of rainforests—feed into this oppressive capitalist system.

The feedlot sector of the game addresses issues on the level of beef production at McDonald’s slaughterhouses. Ranch cattle are collected from the agricultural sector of the game by giant cranes that comically scoop them up unaware, allegorizing the machinery of industrial factory farming. At the feedlot, players must fatten these cattle by feeding them soy fodder with the option to introduce fillers such as industrial waste and hormones to accelerate growth. As consumer demand for hamburgers increases in the game, food production must also quicken, and thus, the unethical and unappetizing decision to incorporate industrial waste and hormones to beef is eventually necessary to maintain productive economies of scale. Doing so results in low quality and sickly livestock, with cows exhibiting symptoms of illnesses such as mad cow disease (or BSE) that must subsequently be exterminated by players lest this contaminated beef make its way into Big Macs and Happy Meals. Although the game makes these burger patties unsavory given this context, it is more a condemnation of factory farming operations than meat-eating. Pedercini acknowledges a broader history of industrial pollution, collateral damage wrought by the accelerating capitalist machine. Because players never forestall the spread of disease among cows and merely exterminate them after the fact, the game suggests that the corporate imperative of speed and efficiency invalidates social responsibilities to public health and common decency.

The regular slaughter of beef cattle allows players to micromanage the fast food sector, in which fry cooks and cashiers turn a profit on cooked meals. At this level, McDonald’s Videogame allows players to directly oversee the employment of individuals at a restaurant. The game equates fast food labor with assembly line production, where fry cooks and cashiers monotonously cycle through the same, repetitive animation of their sole task. These workers begin with a “happy” status, but the tedium of constant, unskilled labor and the overwhelming demand from long lines of customers creates dismal work conditions that lead to a bored and angry workforce. Players have two options to stimulate inefficient workers: give them an award or discipline them. Awarding workers fulfills their happiness temporarily, but because awards can only be given once, players must resort to draconian measures once these workers lose interest in their jobs again. Disciplining employees actually causes little to no effect, and the only viable option afterward is to simply fire the employee and hire a naïve new face. Because all service industry workers will inevitably tire from this assembly line process, players will become complicit in a constant cycle of firing and hiring new workers that perpetuates a system of thankless, exploitative labor. Of course, firing too many workers will cause a labor dispute, in which case players can migrate to the corporate headquarters sector and corrupt a politician to subdue workers’ unions. The game suggests that under a capitalist logic, it’s more cost effective simply to expunge disagreeable workers than to find long-term, constructive solutions to labor issues.

The corporate headquarters addresses the reception of McDonald’s as a brand by allowing players to control both the company’s advertising campaigns and the company’s influence on governmental policy by corrupting public officials. The tutorial satirically reminds players that McDonald’s isn’t simply a fast food chain, but also symbolizes an entire “lifestyle” and “western culture’s superiority.” Players can frame the restaurant as an advocate for the third-world with an advertising campaign that claims that McDonald’s fights world hunger. The game reassures players that “collective western guilt can be leveraged to generate profit,” suggesting that what drives this campaign isn’t a charitable spirit, but rather the unending impulse to exploit consumer markets. The advertising campaign portrays poverty as a “monster coming from the outer space,” reflecting how the causes for poverty is obscured by greedy corporations reluctant to admit their complicity in creating wealth inequalities. Rather, this intangible, fictional scapegoat steers attention from the real, material implications of corporations unwilling to provide a livable wage or disinclined to satisfy demands from striking workers. The game also critiques how food industries have lobbied for misleading dietary guidelines to sell product, allowing players to launch an advertising campaign that suggests how McDonald’s fits in the food pyramid as part of a healthy, balanced diet. Yet another campaign promotes brand awareness among suggestible children by cross-promoting the restaurant with Happy Meal toys, thus indoctrinating consumers at younger ages. Upon criticism by detractors like environmentalists and consumers’ associations, players can oversee public relations campaigns to silence activism. Politicians, health officials, and climatologists can be paid off, and McDonald’s can continue to thrive unopposed. These gameplay mechanics all provide critiques of the restaurant, tackling multiple issues along every level of production and consumption.

With these strategies in mind, we can turn our attention to thinking about how to critique videogames in similar ways. If writers want to seriously engage in a critique of videogames, one must address these intersecting industrial factors beyond single-issue lines. It’s not enough to argue that a game like Horizon Zero Dawn or Uncharted: The Lost Legacy is acceptable because female protagonists and non-white characters are well represented. We also need to look at the conditions of its production to see if workers are also represented in such a way, or if such corrective measures really just conceal real-world, industrial inequalities. From an interview with Jacobin, Pedercini argues, “We have to counter the incredibly common argument that all our high-tech gadgets and modern amenities are gifts of capitalism, and not the result of organized labor.”

All too often, game critics are quick to reward companies for portraying diversity in narratives (I too admit to being guilty of this tendency), but representational politics are just the tip of the iceberg. If we celebrate leading female characters in games, we must also always verify if women are the authors of these characters behind the scenes. Moreover, we must consider if this kind of industrial labor is even fulfilling and equitable to begin with. In a PR move that evokes the awarding of employees in McDonald’s Videogame, Sony PlayStation employees received a retro gift that portrays the company as a kindly entity despite the lingering labor issues that go hand-in-hand with all game corporations. While it projects the image of a progressive, benevolent industry, we must always recognize that the reality of videogame work is one of precarity, where a Naughty Dog employee can be fired for filing a sexual harassment complaint and workers must leverage their own lives for fairer working conditions. These industrial issues raise the stakes of videogame critique, and they must be raised if we want games to contribute to broader cultural and political conversations. Both games and critical writing together must confront the intersecting lines of capitalist production, labor, and consumer reception rather than address isolated fronts, and in doing so, we can reveal the broader mechanisms that uphold industrial dispossession and exploitation.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.