Opened World: Erasing Places

Miguel Penabella compares two games about gentrification.

The Saturday morning cartoon aesthetic of Donut County and and the sterile, featureless city blocks of Nova Alea seem mutually opposed upon first glance, but both games share an interest in examining the deleterious effects of gentrification. Donut County allegorizes gentrification via puzzle game mechanics in which homes and buildings vanish into maneuverable holes, transforming lively city blocks into empty lots for redevelopment by a crooked technology company. Nova Alea is a short pedagogical experiment from developer Molleindustria’s “Playable Cities” series, critiquing the city simulation genre by introducing factors like gentrification and class inequality in players’ endeavors as real estate speculators. While mechanically and aesthetically different, both games task players with reshaping and ultimately destroying their respective cities. Undesirable neighborhoods and residents plunge into ruinous sinkholes in one game, while the towering up of skyscrapers displaces former tenants and bursts the marketplace. Players are positioned as villains aligned with capitalist hegemony, dispossessing land from longstanding communities and reflecting the systemic processes by which underprivileged neighborhoods are displaced by the arrival of outside wealth. Nevertheless, while Donut County lacks deeper lessons other than recognizing our own complicity in gentrification, Nova Alea is far more effective in demonstrating the interconnectedness of capitalism, the creative class, income inequalities, and the displacement of people.

Donut County’s main conceit is simple: players maneuver a hole that expands in size as it gradually devours every object in sight until the level is fully cleared. The player-character BK, a raccoon employee of a doughnut shop obsessively glued to their tablet, controls the terrorizing hole through a dastardly app. Mira, BK’s human coworker, eventually connects BK to a shady legion of raccoon interlopers who seek to seize power of the city with their tech. Throughout the game, displaced residents angrily confront BK, who responds by condescending to them, treating their homes and possessions as trash (he is a raccoon after all). The game is thus about culpability—who is at fault here, and who is ultimately responsible for reversing the disastrous effects of gentrification that has displaced residents 999 feet below Donut County? Many shrewd writers such as Emily Short and Laura Hudson have already examined how Donut County thematizes gentrification, and developer Ben Esposito outright acknowledges that the game is “about erasure” and contends that its story is “interconnected with capitalism and the way cities are run.”

These themes are rooted in real-world parallels, as Donut County borrows from one specific case study: Los Angeles. Though Los Angeles is never explicitly named, the setting is immediately clear to anyone familiar with the city. The giant garbage can that serves as raccoon leader Trash King’s lair lampoons Griffith Observatory; BK’s doughnut shop calls to mind Randy’s Donuts in Inglewood with the pastry adorned atop the kiosk; and characters are even traffic jammed on the 405 highway. Perhaps most applicable to the issue of gentrification is the Gecko Park level, a pun on LA’s Echo Park, a prominent gentrified community alongside other rapidly changing neighborhoods like Silver Lake, Highland Park, the Arts District, and nearby Boyle Heights. The game’s increasing scale—starting small by devouring flowers or fast food containers before swallowing progressively bigger objects like entire apartment buildings as the hole widens—mirrors the processes of gentrification. Activists of the hotly contested Boyle Heights neighborhood understand that gentrification starts small with the emergence of seemingly harmless businesses like coffee shops. Historically, third-wave coffee shops signify the violent, symptomatic spread of a creative class that moves into low-income neighborhoods, driving up rent prices. It’s notable, then, that the villains of Donut County operate through a doughnut shop, evoking this history of yuppie demand for the upscaling of cheap favorites as designer specialties, foodie viral hits marked up beyond reason, and cosmopolitan bakeries and cafés that ultimately reshape cities.

Ben Esposito is no stranger to these ideas, having explored the perspective of the creative class in Brooklyn Trash King and even grappling with his own complicity in cultural appropriation during the development of Kachina, the cancelled predecessor to Donut County. Kachina lifted Hopi themes and imagery before a blog post by Debbie Reese of the American Indians in Children’s Literature (AICL) called Esposito out for appropriation, noting that his equation of Hopi religious systems with folklore and association of teepees and totem poles with Hopi culture is incorrect and exoticizing. The self-victimizing, reward-seeking BK of Donut County thus serves as an authorial surrogate for Esposito. Characters’ chastisement of BK’s insensitivity parallel the developer’s misguided and detrimental real-life attempts to double down on narrating a Hopi story that was never his to tell. While Esposito thankfully wised up to criticisms and apologetically scrapped the project, themes of complicity and responsibility are prevalent throughout Donut County. BK’s narrow-mindedness as he obsesses over his tablet suggests how addictive apps gamify harmful behaviors and distract us from openly communicating with others and realizing potential ethical dilemmas to our online actions.

In an interview with Liz Ohanesian, Esposito further identifies the influx of tech jobs and money as “accelerating the problem,” and indeed, these observations get to the heart of how the videogame industry broadly contributes to the continuing gentrification of cities. For example, the settlement of Ubisoft in low-income neighborhoods such as Montréal’s historic Mile End and Toronto’s industrial Junction Triangle have significantly reshaped these areas, ushering in an outside labor pool of educated professionals and displacing low-income immigrants. Those uncritical of these shifts in racial and class demographics may view such changes as “exciting” or as signs of “revitalization,” but urban redevelopment only benefits the moneyed gentrifiers who recently called these places home. Likewise, the annual hosting of the Game Developers Conference (GDC) in San Francisco actively contributes to the city’s gentrification by lining the pockets of UBM. This billion-dollar business events organizer has, as Bruno Dias notes, “determined that San Francisco is the most profitable place to host GDC” to the detriment of marginalized local game developers increasingly priced out by astronomically expensive conference passes affordable only by corporate players.

While gentrification remains a complex issue with overlapping factors and complicities, Donut County plays it safe, easily solving its problems with a boss fight. BK apologizes for his mistakes and his victims admit that forgiveness will take time, but the real impact of gentrification obviously cannot be solved simply with apologies. Donut County’s lackluster conclusions are fine for a whimsical, casual puzzle game but remain unsatisfying for those seeking greater nuance and critique of corporate abuses so deeply entrenched and felt by gentrified neighborhoods. In contrast, Nova Alea takes a more hardline attitude in its social commentary, portraying gentrification as systemic violence.

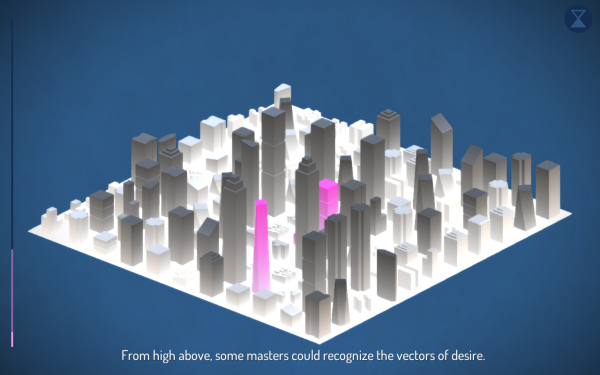

Framed as a historical chronicling of the city of Nova Alea, a coolly detached voice narrates the processes by which wealthy speculators (the player) compete in high-stakes real estate. Players oversee a city abstracted as featureless polygons in a grid, in which squat buildings that grow into tall skyscrapers signify increasing market value wherever such growth occurs. The player’s task is to purchase property when buildings start small and cheap—anticipating where the market will flourish as value migrates across the city over time—and to sell these buildings at a high price before the real estate bubble bursts and your property loses all worth. A winning strategy involves investing in underdeveloped areas in the hope that wealthy, taller skyscrapers nearby will increase the value of smaller buildings by virtue of its proximity. Eventually, grassroots efforts create obstacles akin to rent control ordinances that dramatically decelerate increasing property values or impede it entirely, effectively undercutting that building as a source of profit. Moreover, the introduction of the Weird Folk, marked as green areas on the map, stand in as gentrifying hipsters and a moneyed creative class that the narrator says “attract the animal spirits of the market.” Like gentrifiers, the Weird Folk establish themselves in underdeveloped areas of the map outside the skyscraper real estate bubble—signifying industrial or warehouse districts—re-urbanizing these impoverished spaces and accelerating the growth of property value. As real estate value travels and your aggressive investments radically alter the shape of Nova Alea, purchasing property adjacent to the Weird Folk will eventually displace these communities as skyrocketing rent leads to their own self-destruction. Nova Alea’s abstract demonstration of real estate neatly visualizes the violence of gentrification via the Weird Folk, showing how underprivileged inhabitants are displaced while the player-speculator hoards property as featureless repositories of wealth.

Real estate, Molleindustria argues, is a gamified system played by moneyed capitalists who view cities from a distance, here literally rendered as a bird’s eye isometric view over the city (one imagines a Wall Street executive in a top-floor office with the same vantage point). This privileged perspective recalls Michel de Certeau, who, in his seminal text describes the sensation of peering out from the 110th floor of the World Trade Center and argues that this totalizing view ultimately flattens difference and reinforces uneven power relations. Nova Alea abstracts the city as nothing more than featureless shapes that accrue value and can be sold, thus eliminating trifling concerns of what real life actually looks like on the ground: suffering communities, class inequalities, poverty. The game’s aesthetic allegorizes how these real estate tycoons view the cities they destroy, which the narrator describes as “a matrix of financial abstractions” in contrast to actual residents who see Nova Alea as “a mixture of shelters, connections, memories, longings.” In addition, the game’s isometric view also serves as a critique of city planning games like Sim City or Cities: Skylines. Rather than effortlessly build up megacities without paying heed to real issues like gentrification or income inequality, Nova Alea foregrounds the consequences of unchecked speculation. Moreover, the genre often ignores the historical realities of American cities grappling with the legacy of racial and class inequalities, where racist euphemisms for “urban renewal” mean the demolition of poor black neighborhoods for white residents, what James Baldwin bluntly called “Negro removal.” Molleindustria acknowledges how this genre is dangerous because it equates win states with unrestrained development and profiteering, especially when these games directly influence real urban planning.

As Molleindustria’s Paolo Pedercini asserts in an interview with Pietro Minto, gentrification is not a “direct and inevitable” product of “individual choices,” but is instead institutionally perpetuated via a “system of exclusion” by a reckless financial sphere. This acknowledgement of a broader system pulling the strings of urban development and exclusion differentiates Nova Alea from Donut County. While the latter gestures towards these ideas as BK eliminates the existing social environment so that lots become emptied for later land development, too often the game points fingers at individuals rather than at a broader history and system of power. In contrast, one of Nova Alea’s end states proposes a more meaningful balance that better reflects the tenuous realities of cities today. If the player avoids bankruptcy but never quite breaks through to maximum profitability, the game ends unfinished, in which grassroots activists have managed to partially curb the spread of uncontrolled speculation. Here, the underclass and the moneyed capitalists remain stalemated in the current status quo. Where Donut County quickly forgives the oppressors that nearly ruined its fictionalized Los Angeles, Nova Alea leaves open the room for lasting resistance, in which the city will always be a place of contention so long as a capitalist hegemony endures.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.