Let’s Place: Object Without Filling

Daria Kalugina considers the cube.

I first encountered minimal art when I was studying in art school; it was Tony Smith whose works attracted me in particular. Our tutor quoted a story told by the artist, about the time he traveled on the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike with three of his students:

It was a dark night and there were no lights or shoulder markers, lines, railings or anything at all except the dark pavement moving through the landscape of the flats, rimmed by hills in the distance, but punctuated by stacks, towers, fumes and colored lights. This drive was a revealing experience. The road and much of the landscape was artificial, and yet it couldn’t be called a work of art. On the other hand, it did something for me that art had never done. At first I didn’t know what it was, but its effect was to liberate me from many of the views I had had about art. It seemed that there had been a reality there which had not had any expression in art.

In these quotidian industrial landscapes familiar to many of us—which also re-appear later in the works of David Lynch – Tony Smith saw the end of art.

Tony Smith said his works were on the edge of dreaming, he called them speculation in pure form. His works were usually exhibited outside: plain structures, simple shapes interrupting the complexity of a landscape, like a glitch in the textures, disrupting the order of things with nothing but their presence.

Tony Smith, Die, 1992 Steel, oiled finish, Whitney Museum of American Art www.tonysmithestate.com

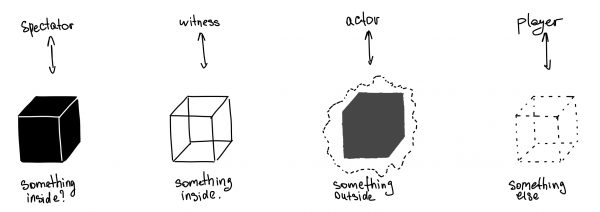

Here is a work of his, titled Die. He created it in 1962; a 6х6х6’ black cube of steel, a weird intervention in reality. It resembles the scale of human body, but doesn’t offer any narrative apart from its shape, color, scale and material. The body of the spectator, the witness of this work, becomes the tool of relation. The only way the work can communicate is to offer this comparison, although it’s not like the work requires this activation by the spectator: in a way, it activates them instead. Accompanied by the double meaning of the title, it compels spectators to extend its finitude to their own body.

Prior to Die, Tony Smith was working on The Black Box in his backyard, when his granddaughter asked him what he wanted to hide in there. This is probably the most beautiful paradox of the minimal artwork—it offers only presence, while hiding the absence inside: being there, while not being there.

Object without feeling

In the first episode of Twin Peaks: The Return, there is a young man assigned to watch a glass box, told only that something may eventually take place inside it. He sits motionless, staring bluntly into the weird, highly aestheticised object in a naked room filled with monitoring equipment and unopened cardboard boxes. His gaze is supported by the cameras, also directed at it—if he misses something, surely the cameras won’t. He watches the box intensively, while the box remains indifferent to the man, until it’s not. As with minimalist art there is a presence and a void; there is an anticipation for something to appear inside; there is a spectator’s body opposed to the object when he experiences it.

Twin Peaks: The Return, 2017

Only this time, the object is not opaque, heavy, and permanently present. It is transparent, elusive, yet judging by the intensive stare of the camera, has something hidden within . One’s gaze does not stumble upon the object, rather it slips right through, prepared to witness something that is yet to come. This time, the finitude of the spectator’s body is not hidden within the object anymore, but bursts out of it. The Glass Box looked back, and its stare was fatal.

Filling without object

I was watching a video on the performance capture work that went into The Last of Us, when I saw them: small, dark grey foam bricks on a table. With a fast movement, the actor swept them all onto the floor, and the rendered scene transposed them into booby-traps and explosives.

As in previous examples, the object relates to the actor’s body as well. But this time, the thing isn’t indifferent, but rather gets activated by the interaction. The actor interacts with a thing which is not yet there. A player sees the digital surface it is wrapped inside, missing out on the real and material thing that gave birth to the in-game object.

While the shape is present in reality, its narrative unfolds somewhere else; being here, while becoming elsewhere. The thing is skinned and solid; there is no void urging to be filled. There is no question what’s inside it, but what it is wrapped in. Changing the surface, it can be anything.

Unlike the specific object, which offers solely its bare presence, the prop flickers with possible narratives, as it can become everything.

The everything

In David OReilly’s Everything, the whole universe consists of flickering objects.

The things are the surfaces, without filling, glitch inside them and you’ll find them hollow. This time, there is no real-world prop to begin with, no structure to wear the surface.

The human is not present in the universe of things, nor is that specific relation to a thing, experienced with one’s body. The human is dissolved into other things that bear anthropomorphic traits. Through dialogue, human emotions emerge: objects talk to the player and to each other as people would. Also, the disembodied voice of philosopher Alan Watts is spread around the game world. The finitude of the human body is represented by its absence in the game, where the presence of any human narrative is enclosed in every object.

The game itself is one such thing—on a rendered playstation and screen it floats among the game’s other objects, in the place where there is no more order, and a molecule, a bug and an airplane all look the same size. As a whole, Everything is a container, filled with every object imagined. As a single in-game thing, it is a surface, hollow and flickering. The Everything itself is a flickering object, constantly turning itself inside out. It doesn’t really need to confront a player, as the game can play itself. Not only it does so by design—when left alone for sometime, the in-game world continue to act on its own, letting a player to opt for a spectator role—this specific quality of an object, that can turn into anything else, opens up a question: if a thing can be anything, can it tell any story? Can this flicker become the narrative engine, that could put on a story as easily as a prop can change its skin?

Daria Kalugina lives in Moscow. Sometimes she works in artistic education, and dreams of building fictional worlds for learning.