Let’s Place: Is This Now?

Daria Kalugina inspects the peculiar flow of time.

A page from Geralt’s journal: I met a desperate and broken man. Someone has cast a curse on his son, causing him to slip closer and closer towards the grave with each passing day. He fears he may have to bury the boy before the next moon. I have to help him before it is too late.

But I’m already overwhelmed with commitments. I try to fit everything into my schedule. I rush to help the man, across the towns, villages, and camps; markets and forests, by rivers and roads. The sun goes down and I worry—might I be too late?

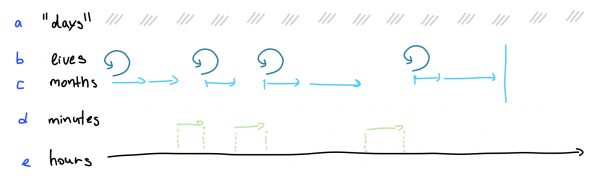

In games, time is split between several layers of different pacing. Cyclical, repeating, unreal time. Games dissect my time, multiplying it into various forms. There is the real time I spend playing the game, and there is a set of conditions that shape the in-game time: the timeflow of the game world, the time where the narrative takes place, the repeating cycles of play and finally the all of the discrepancies, happening between the real and in-game times. I want to draft the map of time in the average videogame world.

days and nights

The sun rises.

Days change into nights, evenings come to replace mornings. Writing this I am flying across the continent, racing towards the sunrise, accelerating time. My night on the plane is condensed by nature. It’s like my time in games is condensed by the core mechanics, while I observe time flow from bird’s eye view, and days of in-game time can fit into hours of my play.

Days change into nights, yet this seeming passage of time doesn’t have any other purpose but to imitate the change of light. It makes me think that my being in the game world is full of events, while those events are disconnected from the time where the narrative unfolds.

Down by Law, 1986 Jim Jarmusch

proceeding through the narrative

It requires action to move time forward, the activation of the narrative. Things change only if player takes a meaningful action reserved by the main quest. Roaming around, doing side quests and errands mostly doesn’t count, meaning when I’m out of the timeline of the general narrative I occupy a special condition wherein things happen, but they don’t take place. Time turns into a space , able to be navigated.

At one of the layers it will be still now when I get to the villagers who asked me for help, even after a week’s worth of the day/night cycle.

The sun goes down.

starting from the beginning

There is something else, when I start from the beginning — I’m not really starting from the beginning, as with each iteration I gain something. Whether I run the game for the second time, to uncover missed possibilities, or simply going over and over again the particular fight I struggle to get through.

Repetition is my friend, my way to improve skills and move forward. Step back, step forward — my way through the game is consistent, yet consists of whirls. These loops are another peculiarity of in-game time. This convention of time, where I revive until I succeed, meets the time I spent playing, in moments of failure, from which I gain experience.

Edge of Tomorrow, 2014, Doug Liman

The other effect of voluntarily engaging with such monotony is the sense of security and control it instils. Learning, enjoying peaceful boredom, or simply making my own metagame, I find value in repetition, even though stuck in these loops I can’t proceed through the narrative, or simply there isn’t one at all.

impossibility of the end of the open world

The sun rises, I’m entering the timeless space. As the time is split between several layers, one would be where I drift through the space, doing nothing. It’s close to where day changes into night, where I die and am reborn. It’s where I’m in charge of time, since the only time unfolding really is the hours I spent on the game.

I can postpone the narrative timeline, developing my skills while doing nothing. But the trap awaits me on approaching the narrative conclusion. As if I’m standing on the edge of the rock and can only peek to the other side, but never jump there. After I beat the boss everything returns to the state prior to the main fight, unable to embrace the changes I achieved, which sometimes, can ruin the narrative itself. There is no value in your actions, after you beat the game, or there is no value in the story, as this weird time-twist plays against it.

I’m left in the timeless space, and the only time to find shelter is in the moment before the fight, before the narrative dissolves, and there is nothing left to move time forward.

The sun goes down.

time played

As minimalist sculpture offered shapes which are exactly what you see, early video art offered similar relation to the time. The time you spent equals the time depicted.

Equal timeframes create the meeting point for the experience of the performer and the spectator. One could say these two roles combine in the figure of the player, who holds all of the various modalities of time together.

Let’s stop for a moment on this synchronization of experience via time, and consider it as an illustrative model that doesn’t have many complications. When my time as the spectator or player equals the time on the screen, it makes another feature visible, rendering the time a context. It adds something crucial to the experience, whether you play remastered classics on a new console, making it a nostalgia machine, or simply the context of the game leaves traces in the game narrative, so that the game becomes a reflection of the context in which it was produced, once again supporting the idea of time working as a place.

There are moments when I control the time—moments when I pause and take a photo. In the real world, when I’m taking a picture of a beautiful landscape, I’m only getting a mask of this escaping moment. The world is living, moving on its own. But when I enter photo mode in a game, it’s not only a mask I’m seeing and this is not a simple pause. Time and everything actually freezes, creating a condition for observation and navigation within the timeless space, no matter how dramatic or dangerous the moment is.

And there are moments when the game interferes with my time, taking over control of it. When the game decides that I played enough, within the framework of repetitive actions. Taking back control from me, time becomes the subject of economic exchange. I spent my gems, for time to go faster, to lift a curse, to skip the cool down, as the wait is the unnecessary and unpleasant surplus.

The sun rises.

In a way the very distinction between the spectator and the player, also lies in the matter of time. The cutscene, my sudden inability to act, leaves me the only option — to watch. Unlike the early video art works, the time in a cutscene isn’t necessarily equal to mine as the player, yet it makes me step away for a moment from this intertwined timelines of the game, as the cutscene doesn’t require my time in order to exist. Instead I invest my time in it again voluntarily, as the only possible unit of control. And before I know it, I’m stranded on the shore of gameplay again, and each of the time flows return to normal.

a) day/night cycle; b) respawn/rebirth; c) narrative unfolding; d) cutscenes interventions; e) time played

I met a desperate and broken man, he fears he may have to bury his son before the next moon. He needs my help.

I rush to help the man, across the towns, villages, and camps; markets and forests, by rivers and roads. I stop to take care of couple of things, just for a moment. The day goes by unnoticed, the sun goes down and I’m probably too late, but I’m going there anyway. As I’m approaching the destination, I see him in the exact same spot, still waiting.

Daria Kalugina lives in Moscow. Sometimes she works in artistic education, and dreams of building fictional worlds for learning.